Born in Hà Tiên, Vietnam in 1968, Dinh Q. Lê is a Vietnamese artist who once lived as a refugee in the US. He lived there with his family after the Vietnam War from 1978 to 1997. In his work, he uses photography, video and installation to explore the topic of the Vietnam War. He conceives his artworks as a sharing platform to know more about the event, even though it remains a sensitive issue in the communist country. Only a few people in Vietnam have recognized the value and importance of his work, but the artist has faith to use it to sensibilise the young generations. Dinh Q. Lê has exhibitions worldwide and is currently preparing exhibitions in the US, Singapore, and France. He currently lives in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam.

You were born in Vietnam and grew up in the US, where you received your art education. Why did you decide to move back to Vietnam?

When I was living in the US, I always felt a little bit like I was in the wrong place. There was no other option but to move to the US. The best you could do is try to stimulate yourself, try to fit in. But in the deep down, it was just off. As you can feel, American culture is very different from the Vietnamese culture. We settled in the California suburbs where we felt isolated and trapped. I tried everything to fit in and stimulate. But in the back of my mind, it was always about Vietnam.

When I graduated, I went back to visit Vietnam for the first time in 1993. As soon as I landed, I walked around, and I just knew that this was the place where I was supposed to be. I felt connected. I also really wanted to learn more about Vietnam War because it played such a crucial part in my life. It’s the cost that let my whole family leave Vietnam. It was something that I never thought of for a child who grew up in Vietnam. It never crossed my mind that one day I would be living in that country.

So I wanted to come back to Vietnam. In the US, the Americans wrote about the war history, about their experience and perspectives of the Vietnam War. But I didn’t see anything that reflected my family’s experience. So that also empathized me to learn more about my country as well. It was a very long process to convince my family. It took four years to go back and forth to Vietnam when it was still a communist country. A part of me did not trust the government, either my family. It was a slow process on many levels, not just about the Vietnamese communist government. When in Vietnam, I realized how very American I was. While in the US, I was too Vietnamese. That always made me feel in the wrong place then it kept me going back and forth, as a blurting process of how to be a Vietnamese again.

Finally, by 1997, I didn’t want to slip my time in America anymore and decided to return to Vietnam. Some of my family were quite hard to understand. Vietnam also has changed a lot with developing transformation. Now they’re a bit envious that I am back while they’re still in America.

Your work is strongly related to your own personal history to Vietnam, and to Vietnam History at large. Have you always been interested in that subject? How have your own critical thoughts and art practice on these topics evolved through time?

When I first came as a refugee in the US, I didn’t want to look back anymore. You tried to forget the Vietnam War and build a new life. The problem is the world doesn’t rely on how you forget it.

Back in America in 1979, Hollywood produced so many Vietnam War movies, constantly. I never went, even to want to see any of them because I didn’t want to think about them. The problem is that the subject appeared on the news, and also your classmates asked about it. That means you couldn’t ignore it because they always came around. By the time I went to college in the third year, I finally decided to learn about the Vietnam War. On many levels, I needed to understand and be able to answer questions that people asked me. I needed to know what happened because I was a kid. The war fell out when I was a 6 or 7 years old little boy.

Sadly the class always talked about American soldier’s experiences in Vietnam rather than the Vietnam War. So I needed to look at the situation based on Vietnamese or American-Vietnamese’s perspectives. I started to do research to make people understand what evolved over the last 20 years. I never set out to create an artwork only about the Vietnam War, but one project led to one another. Soon as you research one particular issue, something outcomes out from those researches.

My thoughts about the Vietnam War have changed so many times. I understood how complex these issues are. On the one hand, it was the silver war. On the other hand, it’s a proxy war between the US, Russia, and China. We had to grapple with all these complexities and tried to come to a turn with it. In terms of art practice and how it evolves through art, political art somehow can be very didactic and very poetic. That’s why I’m attracted to making art. This practice allows me to show complexity and nuances.

Most of your artwork refers to the Vietnam War. What History means to you?

I think history is for whoever gets the platform to write. On the other hand, that’s problematic. In the Vietnam War, the US lost the war but still wrote the history. Interestingly, human capacity to write history which is for the loudest speaker, like Hollywood. So I try to use my narrative to disrupt the history that America is putting out.

I did watch the Hollywood movies about the Vietnam War which was PBS series. They had a long series though I watched only some of them. I prefer to read than to watch because I always felt those scenes were a little bit violent or pornography in a way. It’s because most of the documented images of the Vietnam War were taken by foreign journalists, primarily western journalists. They wanted to show the Vietnamese as victims, but we are more than that.

Would you like to explain your artwork « Crossing The Farther Shore » and what can you share to the younger generation about the past in the nation?

It started with the story of a refugee that was crossing into Australia and Southern Europe. Watching that on the news brought back the memories of my personal experience as a refugee. The article was not interested in their personal stories and thoughts. They prefer tragedies, dramas, and portraying them as a victim. I always tell myself that we are more than that.

When I made Crossing The Farther Shore, it was about my personal experience and other refugees experiences. When we were in the refugee camp, we had no idea where we would end up. We could be in America, Australia, and Europe. As the future was so unknown to us, we never knew what to think about, even me. I couldn’t imagine what would be like to live outside the country. So you only try to hang on to what you have. That was all the memory of Vietnam that I had left behind. Of course, you tried to remember the good times and moments that you want to recall.

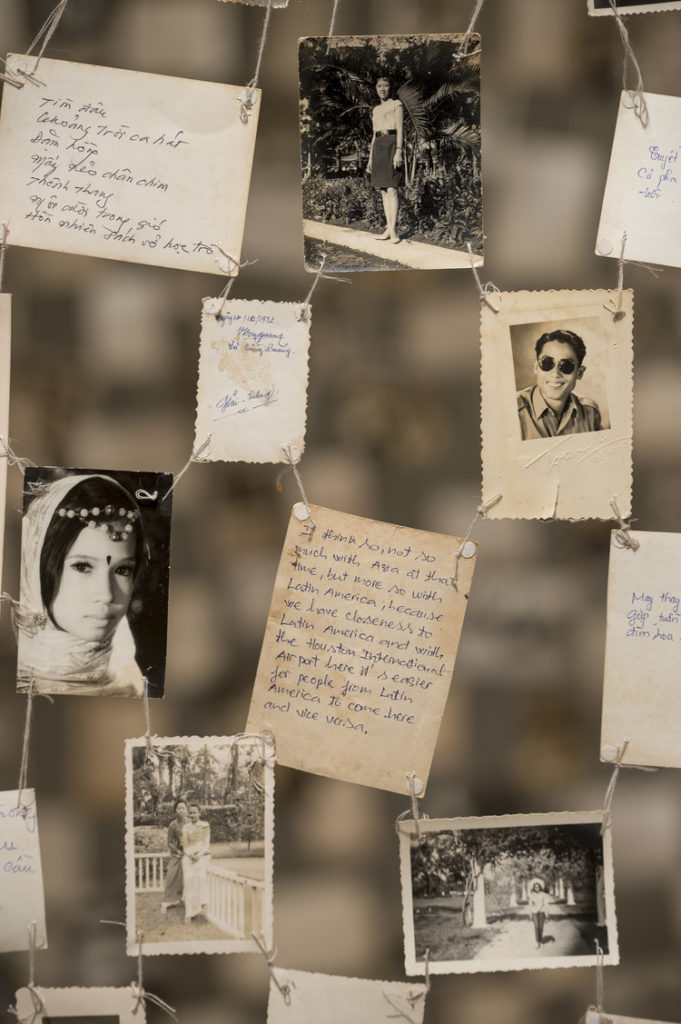

When you see the artwork, it is created like a mosquito net that resembles the refugee camp and a home filled with moments from the past. When we tried to sleep under the mosquito net, our minds went back to all that we held like fear with those memories of the good times. All the pictures of happy moments are our thoughts about ordinary life. It was very different from what the press and newspaper had portrayed us. They have portrayed us as victims of war, drowning, and something. They never really looked at us as just ordinary people who also have lived through delightful times as well back in the time. So I want a work that knowingly remembers and portrays us in a very different way and through our own lenses.

Another attractive project is The Farmers and the Helicopters. It all started from a newspaper article about one farmer and one machine guy who decided to build a helicopter. But the government freaked out because they didn’t know how to control it. Surprisingly, the public supported these guys, and they wrote in the article as a scientist and engineer. They also want to volunteer their services to help make this happen. It was a wonderfully large amount of support and eventually enough pressure for the government to give back the helicopter to them. That was how the story ended. The interest these two guys have in this machine is so unique. I was fascinated by this because the helicopter in the Vietnam War is a very iconic machine. The helicopter before used to evacuate the wounded, and then changed into an armed helicopter. Interestingly, there’s a person who turned a violent machine into something else. Unconsciously, there’s a possibility to transform something that existed in the Vietnam War into something positive. The public started to fully understand while they supported the building of the helicopter.

So I interviewed them and had a wonderful conversation about their childhood memories during the Vietnam War and also their reason for making this helicopter. I created the artwork into a documentary video that includes three channels. The first one is a song, the second is an interview with the two helicopter guys and their relatives about how the helicopter meant to them with its transformation of today. The last one is a short muted clip of Hollywood movies, as well as a documentary clip in the Vietnam War about the helicopter to let the Vietnamese tell their stories for the first time.

When you look at Crossing The Farther Shore’s artwork, you see thousands of pictures of everyday people that everyone can relate to. All the poses of the family picture and every captured moment of it, everybody has them like everyone. Whether they live in Europe, the Philippines, even Indonesia, they’re all the same. That’s what I’m trying to say is that we are more than the Vietnam War. Americans have their own stories to tell, unfortunately they didn’t include us. Those are the issues I have. As you can see, Vietnam War is very complex. If you want to understand it, you have to see all of the perspectives. Particularly to my Vietnamese community, if you want to hear your stories, you have to fight for them and create them.

As for the Vietnamese younger generation, they have been through all of the history of the Vietnam War and the aftermath. We are living in a communist country even though the government doesn’t want to deal with this issue. In some ways, they felt that it was an embarrassing chapter of history. However, it’s not a good idea when we discuss it. I think the young Vietnamese generation currently doesn’t know much of this history. I hope that one day at least, my work can be a sharing tool of these experiences in the future for their generation. We cannot deal with the issue today but, the work will be around in the future.

What is the reception of your artwork in Vietnam? And internationally?

I have a truly complicated relationship with Vietnam because many of my artworks relate to the Vietnam War. It’s so difficult to show my artwork openly here. Vietnam still has strong censorship also particularly the Vietnam War remains a sensitive issue with the Vietnamese government. They surely want to know the better version to be heard. And I have done that to follow that fit into that version. I have worked that contradicts its story version as well. So I haven’t been able to show the work in Vietnam, it’s not possible if I want to show the artwork from a multi-perspective.

At this point, I think many young artists with a limited number of people know about what I do. But in terms of the general population, they only know that I’m an artist and I have made artwork to show them internationally.

As for international scale, there’s been a fascinating mixture about the reception of my work for a long time. America was a primary place where I showed my work. I think Americans were interested in my artwork because they needed more perspective about the Vietnam War. On the other hand, Europeans were fully tired of it. They didn’t even want to see anything related to the Vietnam War. So that’s why they never picked me up for some exhibition or out where besides the US. Now they are currently garbled and they deal with this issue that I’ve been working on, representation of the horrible memories of wars. It took time and place to understand it, but my work has been showed in Europe quite much

As for Asia, I wasn’t considered a Vietnamese artist when I first moved back because I grew up in America. So many Asian curators thought that I wasn’t qualified. As time goes by, things have changed a lot today because so many artists studied abroad, living there, and going back, now they slowly see me as a Vietnamese artist.

What are your future projects?

I am currently working on the exhibition for my gallery in the US. The title is called Monuments and Memorials. It’s a combination with a previous project I have worked on in Singapore last year or two years ago. It’s very interesting the distance or in between monuments and memorials and how valuable and interchangeable they are.

I’m working at the National Gallery of Singapore for a virtual and offline project ‘Voices in the center’ in June which is quite different from what I’ve done before. The curator wanted me to participate but I’m very nervous because of my political-themed artwork. Basically, the project will create an app which will launch online firstly around May. It’s an app that can take weaving for a year through signature digital photographs. It’s very useful for kids to discover the artwork.

The last project is a small solo survey exhibition with Quai Branly Museum in Paris, France. It will be held in February 2022 and I hope that I can have a chance to travel to Europe soon.

Interview by Amirahvelda Priyono – March 2021

Né à Hà Tiên, Viêt Nam en 1968, Dinh Q. Lê est un artiste vietnamien qui a vécu comme réfugié aux États-Unis. Il s’y est installé avec sa famille après la guerre du Viêt Nam de 1978 à 1997. Dans son travail, il se sert de la photographie, de la vidéo et de l’installation pour explorer le thème de la guerre du Viêt Nam. Il conçoit son oeuvre comme une plateforme d’échange pour mieux connaître cet événement, même s’il reste un sujet très sensible au sein du pays communiste. Seules quelques personnes au Viêt Nam ont saisi la valeur et l’importance de son travail, mais l’artiste ne perd pas espoir de pouvoir un jour l’utiliser comme un outil de sensibilisation pour la jeune génération. Dinh Q. Lê est exposé dans le monde entier, et prépare actuellement des expositions aux États-Unis, à Singapour, et en France. Il vit actuellement à Ho Chi Minh City, Viêt Nam.

Vous êtes né au Vietnam et avez grandi aux États-Unis, où vous avez reçu votre éducation artistique. Pourquoi avez-vous décidé de revenir au Vietnam?

Quand je vivais aux États-Unis, je me sentais toujours un peu au mauvais endroit. Il n’y avait pas d’autres options que de partir. Le mieux que l’on puisse faire est d’essayer de se stimuler et de s’intégrer. C’était à peu près ce que j’ai fait. Comme vous pouvez le constater, la culture américaine est très différente de celle du Vietnam. Nous nous sommes installés dans une banlieue californienne, où nous nous sentions isolés et piégés. J’ai tout essayé pour m’intégrer et me stimuler, mais au fond de moi le Vietnam revenait toujours .

Lorsque j’ai obtenu mon diplôme, je suis retourné au Vietnam pour la première fois en 1993. Dès que j’ai atterri, j’ai su que c’était l’endroit où je devais être. J’avais réellement envie d’en apprendre plus sur la guerre du Vietnam parce qu’elle joue un rôle crucial dans ma vie. C’est à ce prix que toute ma famille a pu quitter le Vietnam pour finir aux États-Unis. Et c’est quelque chose auquel je n’avais jamais pensé en tant qu’enfant ayant grandi au Vietnam. Je n’aurais jamais imaginé vivre un jour dans ce pays.

Aux États-Unis, les américains ont écrit sur l’histoire de la guerre du Vietnam à propos de leur expérience et la perspective qu’ils avaient de celle-ci. Mais je n’ai rien vu qui témoignait de l’expérience qu’a connu ma famille. C’est également ce qui m’a poussé à en apprendre davantage sur mon pays. Il aura fallu quatre longues années pour convaincre ma famille de faire d’aller au Vietnam. car moi et ma famille n’avions pas confiance en ce gouvernement. C’était long sur plusieurs niveaux, et pas seulement au sujet du gouvernement communiste vietnamien. Quand je suis arrivé au Vietnam, j’ai réalisé à quel point j’étais très américain. Aux États-Unis, j’étais trop vietnamien. Je me suis donc toujours senti au mauvais endroit, et j’ai continué à faire des allers-retours, comme un processus flou sur comment être à nouveau vietnamien.

Finalement, en 1997, j’ai décidé de ne plus perdre mon temps aux Etats-Unis et de retourner définitivement au Vietnam. Certains membres de ma famille avaient du mal à comprendre, mais le Vietnam avait également beaucoup changé. Maintenant, ils sont un peu envieux alors qu’ils sont encore aux Etats-Unis.

Votre travail est fortement lié à votre propre histoire personnelle avec le Vietnam, ainsi qu’à l’histoire du Vietnam dans son ensemble. Avez-vous toujours été intéressé par ce sujet ? Comment vos propres pensées critiques et pratiques artistiques sur ces questions ont-elles évolué au fil du temps?

Quand je suis arrivé en tant que réfugié aux États-Unis, je ne voulais plus regarder en arrière. Vous oubliez la guerre du Vietnam, bâtissez une nouvelle vie. Le problème, c’est que le monde ne dépend pas de la façon dont on l’oublie.

Aux États-Unis en 1979, Hollywood produisait beaucoup de films sur la Guerre du Vietnam. Je n’allais jamais les voir car je ne voulais pas y penser. Le problème est qu’on ne pouvait pas ignorer le sujet, il apparaissait aux informations et que mes camarades de classe s’y intéressaient. Lorsque je suis allé à l’Université, en troisième année, j’ai finalement décidé de me renseigner à ce propos. À bien des égards, j’avais besoin de comprendre et de pouvoir répondre aux questions que les gens me posaient. J’avais besoin de savoir ce qui s’était passé quand j’étais un petit garçon de 6 ou 7 ans.

Malheureusement, en classe nous parlions surtout de l’armée américaine plutôt que de la guerre en elle-même. Je me devais donc d’appréhender l’histoire d’un point de vue vietnamien ou américain-vietnamien. J’ai donc commencé à lire et faire des recherches afin de faire comprendre aux gens que l’histoire avait évoluée au cours des 20 dernières années. Je n’ai jamais eu l’intention de créer mon œuvre uniquement sur la guerre du Vietnam, mais un projet a mené l’un à l’autre. Dès que vous effectuez des recherches sur des questions particulières, quelque chose en ressort.

Mon appréhension à propos de la guerre du Vietnam a changé plusieurs fois et j’en ai toujours vu la complexité. C’était une guerre économique et d’un autre côté, c’était une guerre par procuration entre les États-Unis, la Russie et la Chine. Nous avons donc dû nous accrocher à toutes ces complexités et tenter de s’en sortir. D’un point de vue artistique, l’art politique est d’une certaine manière très didactique et très poétique. Cette pratique me permet de montrer la complexité et les nuances des choses.

La plupart de vos œuvres se réfèrent à la Guerre du Vietnam, que signifie l’histoire pour vous ?

Je pense que l’histoire est pour quiconque obtient un moyen d’écrire, mais d’un côté, c’est problématique. Pendant la guerre du Vietnam, les États-Unis ont perdu la guerre mais écrivent encore l’histoire. Fait intéressant, la capacité à écrire l’histoire revient souvent à celui qui parle le plus fort, avec Hollywood par exemple. Alors quel que soit le médium que j’utilise, j’essaie d’en faire usage pour perturber l’histoire que les Etats-Unis imposent.

J’ai regardé des films hollywoodiens sur la guerre du Vietnam, qui étaient sur le service public. Même si je préfère lire que de regarder parce que j’ai toujours eu l’impression qu’il y avait un sens pornographique et violent dans certaines des scènes. C’est parce que la plupart des images documentées de la guerre du Vietnam ont été prises par des journalistes étrangers, principalement des journalistes occidentaux. Ils voulaient montrer les Vietnamiens comme des victimes. Nous sommes plus que cela.

Pouvez-vous expliquer votre œuvre “ Crossing the Farther Shore” et que pouvez-vous transmettre aux jeunes générations à propos du passé national ?

Le projet a commencé suite à l’histoire d’un réfugié qui a traversé l’Australie et l’Europe du Sud. Voir cela aux informations m’a rappelé mon expérience personnelle de réfugié. Les articles à ce propos ne s’intéressent pas aux histoires personnelles des réfugiés, ils préfèrent raconter des tragédies, des drames et les dépeindre comme étant des victimes. Je me dis toujours que nous sommes plus que cela.

Quand j’ai réalisé “Crossing the Farther Shore”, je pensais aussi bien à mon expérience personnelle de réfugié qu’à celles d’autres réfugiés. Lorsque nous étions dans le camp de réfugiés, nous ne savions pas où nous allions nous retrouver. Nous pouvions être aux Etats-Unis, en Australie et en Europe. Comme l’avenir nous était si inconnu, nous ne savions jamais à quoi penser, même moi. Je ne pouvais pas imaginer ce que ce serait de vivre en dehors du pays. Donc, vous essayez seulement de vous accrocher à ce que vous avez. C’est le souvenir que j’ai laissé derrière moi au Vietnam, et bien sûr, on essaie de se rappeler aussi des bons moments.

Quand vous voyez l’œuvre, elle ressemble à une moustiquaire, cela est une évocation des camps de réfugiés, un foyer rempli de moments passés. La typologie de photographies que j’ai utilisé a été orientée par mon envie de me souvenir de moments heureux, où l’on se raccroche les uns aux autres. Toute image positive devrait être un souvenir de la vie ordinaire. C’était très différent de comment la presse nous décrivait. Ils ne nous ont jamais vraiment regardés comme des gens ordinaires qui auraient également vécu des moments agréables ainsi dans le passé. Je souhaite donc réaliser un travail de souvenir réalisé à partir de notre propre point de vue.

L’un de mes autres grands projets est “ The Farmers and the Helicopters ». Tout a commencé par un article de journal au sujet d’un agriculteur et d’un ingénieur et qui ont décidé de construire ensemble un hélicoptère. Mais le gouvernement a paniqué parce qu’il ne savait pas comment le contrôler, et ils ont donc trouvé une excuse dans l’article pour expliquer que ces agriculteurs ne savaient pas ce qu’ils faisaient. Étonnamment, le public a soutenu ces personnes et voulait également offrir bénévolement leur service pour y arriver. C’était un soutien extrêmement important et qui a exercé suffisamment de pression sur le gouvernement pour leur rendre l’hélicoptère. C’est comme ça que l’histoire s’est terminée.

L’histoire de ces deux personnes est unique. J’ai été fasciné car au Vietnam, l’hélicoptère de guerre est un outil emblématique. Avant d’être armé et de devenir une arme mortelle, il servait à évacuer les blessés. C’est intéressant, une personne qui transforme un outil de guerre en une autre chose. Inconsciemment, il y a donc une possibilité de transformer quelque chose qui existait à l’époque de la guerre du Vietnam en quelque chose de positif. Les gens ont donc compris ce principe et ont encouragé la rénovation de l’hélicoptère.

Je les ai donc interviewés et j’ai eu une merveilleuse conversation sur leurs souvenirs d’enfance pendant la guerre du Vietnam et aussi la raison qui les a poussés à faire cette rénovation. L’œuvre est une installation-vidéo, comprenant trois chaînes différentes. La première est une chanson et la seconde est une interview avec les personnes de l’hélicoptère ainsi que leurs parents, à propos de cette nouvelle transformation et de ce qu’elle signifiait pour eux. La dernière est un court clip en sourdine de films hollywoodiens, accompagné d’un documentaire sur la guerre du Vietnam portant sur l’hélicoptère, afin de permettre aux Vietnamiens de raconter leurs histoires pour la première fois.

Que voulez-vous que vos œuvres communiquent au public – en particulier vietnamien – sur la transmission culturelle et l’identité ?

Quand vous regardez “Crossing your Farther Shore”, vous voyez des milliers de photos de gens ordinaires, que chaque personne peut comprendre. Toutes les poses de photos de famille et chaque instant capturé peuvent être familières. Qu’ils vivent en Europe, aux Philippines ou même en Indonésie, les gens sont tous pareils. C’est ce que j’essaie de dire, c’est que nous sommes plus que liés à la guerre du Vietnam.

Les américains ont leurs propres histoires à raconter, mais malheureusement, elles ne nous incluent pas. Comme vous le voyez, la guerre du Vietnam est très complexe. Si vous voulez la comprendre, vous devez en voir toutes les perspectives. Particulièrement pour la communauté vietnamienne, si vous voulez entendre vos histoires, vous devez vous battre pour elles et les créer.

En ce qui concerne la jeune génération vietnamienne, elle a vécu toute l’histoire de la guerre du Vietnam et ses conséquences. Nous vivons dans un pays communiste, même le gouvernement ne veut pas s’attaquer à ce problème. À certains égards, ils estimaient que c’était un chapitre gênant de l’histoire. Cependant, ce n’est pas une bonne idée d’en parler. Je pense que la jeune génération vietnamienne ne connaît pas beaucoup cette histoire et j’espère qu’un jour au moins, mon travail pourra être un outil de partage de ces expériences à l’avenir pour cette génération. On ne peut pas traiter de cette question aujourd’hui, mais le travail va se faire à l’avenir.

Comment est reçue votre œuvre au Vietnam ? Et à l’international ?

J’ai une relation très compliquée avec le Vietnam, car beaucoup de mes œuvres sont liées à la guerre du Vietnam. C’est si difficile de montrer mon œuvre ouvertement ici. La guerre du Vietnam reste un sujet sensible pour le gouvernement vietnamien. Ils veulent être sûrs de quelle est la meilleure version racontée à devoir être entendue. J’ai travaillé sur une version qui s’adapte à la leur, mais j’ai aussi travaillé sur une autre qui la contredit. Je n’ai donc pas été en mesure de montrer mon travail au Vietnam. Ce n’est pas possible si je veux montrer l’œuvre d’un point de vue multi-perspectif.

En ce moment, je pense qu’un nombre limité de jeunes artistes sont familiers de mon travail. Mais pour ce qui est de la population en général, ils savent seulement que je suis un artiste et que j’ai fait des œuvres d’art pour les montrer à l’échelle internationale.

À l’international, il y a depuis longtemps une intéressante réception de mon travail qui est très variée. Les Etats-Unis sont l’un des premiers pays où j’ai exposé. Je pense que les Américains étaient intéressés par mon travail car ils ont besoin de perspectives différentes sur la guerre du Vietnam. D’un autre côté, les Européens en avaient assez. Ils ne voulaient même pas voir quoi que ce soit lié à la guerre du Vietnam. C’est pour cela qu’ils ne m’ont jamais sollicité pour une exposition. Je me souviens des dix dernières années où les pays européens ont traité le problème des réfugiés, à cause des guerres dans d’autres pays. Ils ont donc ce problème, celui de la terrible représentation des souvenirs de guerres. Lentement, mon travail s’est finalement montré en Europe, mais il aura fallu du temps pour qu’ils comprennent.

En Asie, je n’étais pas considéré comme un artiste vietnamien quand je suis revenu, car j’avais grandi aux États-Unis et beaucoup de conservateurs asiatiques pensaient que je n’étais pas assez qualifié. Le temps a passé, et beaucoup d’artistes ont commencé à étudier et travailler à l’étranger avant de revenir, je suis donc devenu pour eux progressivement un artiste vietnamien.

Quels sont vos projets futurs ?

J’en ai plusieurs, je travaille notamment sur une exposition dans ma galerie aux États-Unis, intitulée “ Monuments and Memorials ”. C’est une combinaison avec un projet précédent sur lequel j’ai travaillé à Singapour l’an dernier ou il y a deux ans. C’est très intéressant de voir la distance entre les monuments et à quel point ils sont précieux et interchangeables.

Je travaille également à la National Gallery de Singapour pour un projet virtuel, « Voices in the Center », qui sera exécuté en juin, et qui est très différent de ce que j’ai l’habitude de faire. Le conservateur veut que j’y participe, mais je suis assez nerveux compte tenu de la dimension politique de mon travail. Ce projet sera à l’origine de la création d’une application qui sera lancée autour du mois de mai.

Mon dernier projet est une petite exposition avec le Musée du Quai Branly en France. Elle sera présentée en 2022 et j’espère que j’aurai bientôt la chance de voyager en Europe.

Entretien réalisé par Amirahvelda Priyono – Mars 2021