English version below

Thomas Sauvin est un artiste et collectionneur français. Il travaille sur la photographie vernaculaire chinoise à travers son projet « Beijing Silvermine », une immense archive de près de 850 000 photographies, fondée en 2009.

ACA project : Pouvez-vous nous parler de votre parcours et de votre lien avec la langue chinoise ?

Thomas Sauvin : Tout a commencé avec le fait qu’enfant j’étais dyslexique. J’étais dans un collège parisien dans lequel je pouvais choisir le chinois en 2e langue. J’ai aimé le lien entre la langue chinoise et le dessin. Je me suis dit qu’apprendre une langue dans laquelle il n’y a pas d’alphabet serait une bonne manière de contourner ma dyslexie. C’est comme ça que j’ai commencé le chinois. J’ai ensuite eu l’opportunité de faire un échange dans une famille à l’âge de 17 ans à Pékin et je suis tombé amoureux de la ville. Après le bac, je voulais continuer mon apprentissage de la langue chinoise. J’ai alors fait une école de management avec un cursus qui m’a permis de partir trois ans en Chine.

Comment s’est développé votre intérêt pour la photographie ?

Pendant mes études en Chine, j’ai pas mal suivi les festivals de photo et notamment les premières éditions du festival de Pingyao, fondé par Alain Jullien et Si Sushi. En 2005, Alain Jullien était commissaire indépendant de la Biennale de Photographie du Musée de Canton qui a été un événement assez marquant dans l’histoire de la photographie contemporaine chinoise. C’était la première fois qu’il y avait un vrai travail académique de fait sur la photo. Il a ensuite travaillé pour le festival de Lianzhou. J’avais suivi son parcours et suite à mon diplôme en 2006, je l’ai contacté afin de travailler avec lui. Je suis donc devenu l’assistant d’Alain Jullien à la fin de la Biennale de Canton et au début de la 2eédition du festival de Lianzhou en 2006. Je faisais un peu de tout, de la traduction à l’accrochage des photos.

Après cette expérience au festival de Lianzhou, comment avez-vous commencé à travailler pour « Archive of Modern Conflict » ?

À la fin du festival, Alain Jullien m’a fait rencontrer Timothy Prus, invité à Lianzhou pour présenter une exposition. Il travaillait pour une collection privée londonienne, « Archive of Modern Conflict », créée en 1993 et spécialisée dans la photographie vernaculaire et plus particulièrement l’expérience de la guerre par la population à travers la photographie. En 2006, dans le contexte pré-Jeux Olympiques, il y avait un engouement pour l’art contemporain chinois et Timothy Prus a compris que c’était le moment de collectionner la photographie chinoise. Parlant chinois et connaissant les photographes, il m’a confié la mission de collectionner pour eux. Il avait identifié 90 tirages au festival de Lianzhou et m’a demandé de contacter les photographes, négocier et superviser l’acquisition. Je n’avais aucune formation en art ou en marché de l’art et c’est ce qui leur a plu. Je correspondais à leur état d’esprit qui est de sortir des sentiers battus. J’ai beaucoup aimé travailler avec eux car ils ne cherchent pas du tout à suivre les tendances. J’ai travaillé pour eux pendant neuf ans et je les ai aidés à acquérir quelques 5500 tirages.

Quand et comment avez-vous commencé à collectionner pour vous ?

Avec « Archive of Modern Conflict », je traitais majoritairement avec des photographes contemporains. Progressivement, au gré de mes voyages en Chine, j’ai commencé à fréquenter les marchés aux puces et à y acheter de la photographie dite vernaculaire, donc prise sans intention particulière. Ce qui guidait mon choix c’était l’intention de surprise, je voulais être surpris, trouver quelque chose auquel je n’avais pas pensé. J’ai commencé comme ça à collectionner pas mal d’albums mais rapidement j’ai fait le tour des marchés aux antiquités et je me suis tourné vers internet. Je me suis mis à énormément acheter sur ces sites là et notamment beaucoup de photographie argentique.

Comment êtes-vous passé de « Archive of Modern Conflict » à « Beijing Silvermine » ?

J’ai arrêté de travailler pour « Archive of Modern Conflict » en 2014. « Beijing Silvermine » est né d’une réflexion que je me suis faite un jour : je collectionnais beaucoup de photographie argentique pour moi et pour « Archive of Modern Conflict » mais je ne voyais jamais les négatifs. Je me suis alors mis en quête de ces négatifs. C’est comme cela que j’ai rencontré en 2009 une personne travaillant à Pékin dans une zone de recyclage de déchet contenant du nitrate d’argent, dont des négatifs. C’est ainsi que l’aventure « Beijing Silvermine » a commencé.

Quel travail réalisez-vous sur ces négatifs ?

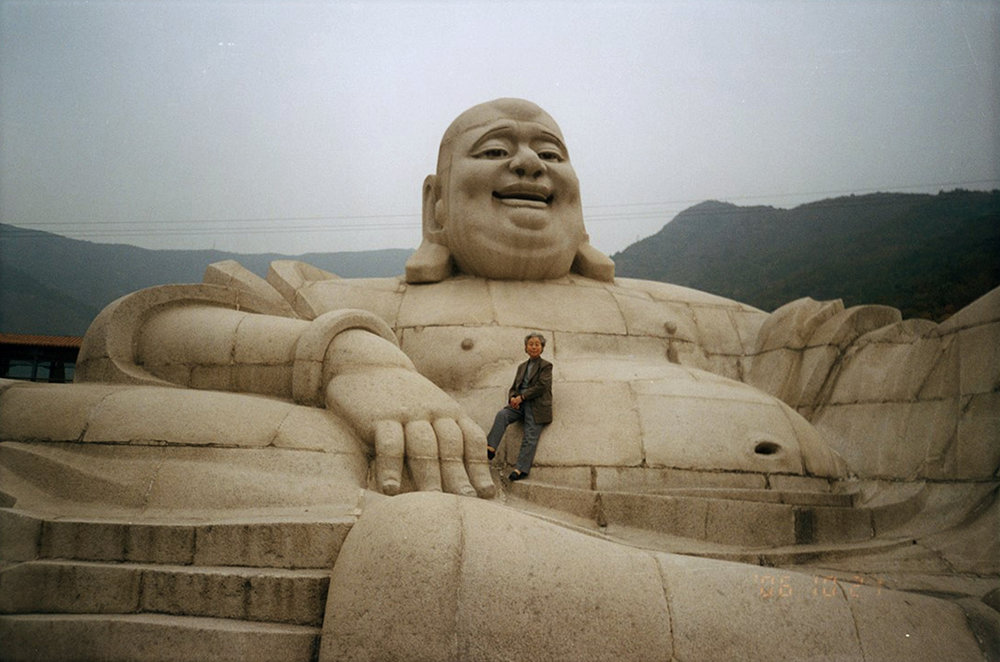

Pendant longtemps, le cœur de la collection a été un pêle-mêle d’images de chinois de tous les jours se prenant en photo dans les endroits les plus connus de Chine. Une grande partie de mon travail repose sur l’observation. Cela fait dix ans que je regarde ces photos tout en restant attentif à ce qui peut émerger de cette observation. Je traduis ensuite cela en faisant des livres, des expositions et des collaborations. C’est cela qui permet à l’archive de vivre.

Je garde tous les négatifs que j’achète. Il arrive que certains négatifs m’intéressent pour un projet particulier plusieurs années après. Au début, je triais beaucoup, je cherchais la pépite. Dans les deux premières années de l’archive, j’avais délibérément mis de côté les images liées au mariage, pensant ne pas les utiliser. Finalement cinq ans plus tard, je les ai utilisées pour mon livre « Until death do us part ».

Quel est votre processus de travail quand il s’agit de réaliser un livre ou une exposition ?

La dynamique entre les expositions et les livres n’est pas la même. À force d’étudier l’archive, j’ai des thématiques qui émergent et que je garde en tête jusqu’à en faire des livres. Cela me permet aussi d’avoir des choses à proposer lorsque je suis approché pour participer à une exposition. Pour les radis que j’expose actuellement à Shenyang, cela faisait un moment que j’avais cette collection de photos de radis et que je la regardais. Lorsque Jérémie Thircuir, le commissaire de l’exposition, m’a parlé du projet d’exposition sur la ferme au K11, j’ai tout de suite pensé à cette série. Ce qui est aussi de plus en plus compliqué, c’est la notion d’exclusivité et de fraicheur que recherchent les institutions. Certaines expositions me demandent plus d’une année de travail pour une exposition qui ne sera au final montrée que quelques mois. Il en va de même avec les livres.

Comment sont guidés vos achats ? Y a-t-il des périodes qui vous intéressent en particulier ?

Je n’ai pas de période de prédilection mais j’ai plusieurs axes qui me guident. Tout d’abord, je ne cherche pas à collectionner ce que les autres collectionnent. Je n’ai rien datant d’avant 1949. Ensuite, je suis guidé par la technique. Les albums sont principalement datés de 1949 à 1980 et les négatifs couleurs de 1985 à 2005, soit de l’introduction de la technique à l’arrivée du numérique. Les limites de l’archive s’imposent ainsi d’elles-mêmes, de part la nature des photographies que je collectionne. Enfin, j’ai une dernière règle, je n’achète jamais rien de cher. Il y a également un dernier aspect qui m’anime, c’est le fait d’acheter des photos qui étaient sur le point de disparaître, d’être détruite.

Je continue toujours à acheter, surtout sur internet, à un rythme d’environ 5 à 6 albums par mois. J’ai également beaucoup acheté de tirages individuels et je dois avoir quelque chose comme près d’1 million de négatifs achetés dans cette fameuse zone de recyclage des déchets de nitrate. Exploiter tous ces négatifs demande un travail considérable. Je travaille avec une personne à temps plein pour la numérisation des négatifs.

Y a-t-il beaucoup d’autres collectionneurs de photographie vernaculaire chinoise ?

Il commence à y avoir quelques collectionneurs chinois assez actifs mais nous ne collectionnons pas la même chose. Ils ont un rapport assez particulier avec l’histoire qui fait qu’ils recherchent principalement des photographies datant d’avant 1900.

Est-ce que vous sentez une différence dans la réception de votre travail entre le public chinois et le public occidental ?

Que ce soit des Chinois ou des Occidentaux, il m’est arrivé de faire face à des gens qui ne comprennent pas qu’on puisse exposer des photographies d’anonymes, sans autorisation. Mais le projet est globalement bien reçu, pour des raisons différentes. En dehors de Chine, c’est bien reçu car l’archive dresse un portrait très différent des clichés que l’on a généralement sur la Chine. Cela exporte un visage de la Chine auquel les gens ne sont pas habitués et donne un aperçu historique sur le Pékin des années 1980-90. Il y a aussi une dimension universelle qui participe au succès de l’archive. On ne parle plus seulement de la Chine et des chinois mais j’aborde des thèmes tels que le souvenir, la famille, l’être aimé. Je me suis rendu compte de cette portée universelle lors que j’ai montré ce projet pour la première fois en Europe lors du festival Format à Derby en 2012/2013. J’ai eu des réactions inattendues de visiteurs me disant se reconnaître dans les photographies prises.

Les Chinois quant à eux sont souvent étonnés de voir qu’on peut écrire l’histoire de la Chine uniquement avec des témoignages, des images des gens de tous les jours. Au début, quand je parlais du projet à des amis chinois, ils ne voyaient pas l’intérêt. Ils me disaient posséder les mêmes images chez eux et ne voyaient pas leur valeur artistique car il s’agit de photographie amateur, ni leur valeur historique car trop proche dans le temps.

A côté de sa dimension artistique, « Beijing Silvermine« possède également une valeur sociologique, qui a d’ailleurs suscité l’intérêt de plusieurs chercheurs. Pouvez-nous nous parler de ces collaborations ?

L’archive a effectivement donné lieu à des collaborations – avec des sociologues, des chercheurs, des étudiants en thèse… – dont deux que je trouve particulièrement notables : une collaboration avec l’Université de sociologie de Pékin, et une pour un web documentaire pour France Culture.

Le premier projet, mené par l’urbaniste français basé à Pékin Jérémie Descamps, était une réflexion sur la question de la mobilité. J’ai réalisé un album réunissant 82 photos de tous types – images de propagandes, photographies de studio, d’auteur et d’amateurs, historiques et contemporaines – autour de cette thématique, qui a servi d’outil d’interview aux sociologues. Ils se sont servis du pouvoir de l’image pour entrer dans l’univers du sentiment, en demandant aux personnes interviewées de sélectionner 6 images et de raconter ce qu’elles leurs évoquaient.

Le documentaire pour France Culture, également en collaboration avec l’urbaniste Jérémie Descamps et réalisé par Victoria Jonathan, porte sur l’évolution de la ville de Pékin entre 1992 et aujourd’hui, en mettant en regard une image d’archive face à sa contrepartie contemporaine.

Et vous, comment vous positionnez-vous par rapport à l’archive ?

Ce qui est intéressant pour moi c’est d’avoir cette position entre distance et proximité. À la fois je porte le regard distant d’un étranger sur une autre culture que la sienne mais en même temps avec une certaine proximité physique car je me trouvais alors à Pékin quand j’ai démarré ce projet, ville dans laquelle la majorité des photos de « Beijing Silvermine » ont été prises. J’étais en même temps curieux de découvrir ce qu’était la ville de Pékin avant que j’y arrive à travers les photographies que je trouvais. Je travaille seulement avec des photos privées, anonymes, qui ne traitent que d’une histoire et narration personnelle mais qui au sein de cette archive immense ne racontent alors plus seulement une histoire personnelle mais passe dans la mémoire collective grâce à des thèmes transversaux. Il y a une dimension de voyeurisme avec le fait de ne travailler qu’avec des photos trouvées. Mais il y a aussi la possibilité d’adopter des positions éthiques dans la manière d’utiliser les images.

Considérez-vous que vous êtes artiste ?

Oui, en effet. Je considère que j’ai plusieurs casquettes, celle du collectionneur quand il s’agit d’amasser des photos et celle d’artiste quand il s’agit de produire quelque chose à partir des photos. Je ne me vois pas par contre comme un photographe ou un éditeur.

Pouvez-vous nous parler de votre activité de commissaire d’exposition ?

De manière anecdotique, j’ai aussi la casquette de commissaire d’exposition. On peut notamment évoquer le travail que j’ai effectué avec Feng Li, de Chengdu. J’ai découvert son travail lors de la biennale de photographie de Canton en 2005. Nous sommes ensuite restés en contact grâce à « Archive of Modern Conflict », avec laquelle nous avons effectué plusieurs acquisitions de ses travaux. En 2016, je décide d’organiser une exposition de son travail à Paris car il était alors inconnu en France malgré sa réputation déjà faite en Chine. Il a ensuite remporté le Discovery Award du Jimei x Arles festival et j’ai exposé son travail aux Rencontres d’Arles l’année suivante.

Quel futur envisagez-vous pour « Beijing Silvermine » ?

Idéalement le dénouement de ce projet serait que toute la collection soit acquise par un musée national ou une institution en Chine.

Quels sont vos futurs projets ?

J’expose actuellement une sélection de photographies de radis dans le cadre de l’exposition « The Farm » au K11 de Shenyang.

Je viens également de publier une édition de tirages de Feng Li, « Pig ».

Propos recueillis par Camille Despré et Lou Anmella-de Montalembert – Paris, décembre 2019

Thomas Sauvin is a French artist and collector. He works on Chinese vernacular photography through his project named “Beijing Silvermine”: a huge archive of nearly 850,000 photographs, founded in 2009.

ACA project: Could you tell us about your background and your link to the Chinese language?

Thomas Sauvin: It all started with the fact that I was a dyslexic child. During my teenager years in Paris, I was a student in a school offering to learn Chinese as a second language. I liked the link between the Chinese language and drawing. I was thinking that studying a language in which there is no alphabet would be a good way to get around my dyslexia. This is how I started to learn Chinese. Later, at the age of 17, I had the opportunity to participate in an exchange program with a Beijing based family and I fell in love with the city. As I wanted to carry on learning Chinese after my high school diploma, I chose to enroll in a French business school allowing me to study in China for three years.

How did you develop your interest in photography?

During my studies in China, I followed a lot of photo festivals and in particular the first editions of the Pingyao festival, founded by Alain Jullien and Si Sushi. In 2005, Alain Jullien was an independent curator for the Biennial of Photography at the Canton Museum – a quite significant event in the history of contemporary Chinese photography. It was the first time that a real academic work on photography was made. He then worked for the Lianzhou Festival. I had followed his career and, after my graduation in 2006, I contacted him to work together. So, I became Alain Jullien’s assistant in 2006, when the Canton Biennial was finishing and the 2nd edition of the Lianzhou festival was starting. I was doing a little bit of everything, from translation to hanging photos.

After this experience at the Lianzhou Festival, how did you start working for “Archive of Modern Conflict”?

At the end of the festival, Alain Jullien introduced me to Timothy Prus who had been invited to present a show in Lianzhou. He worked for a private collection in London created in 1993, “Archive of Modern Conflict”, specialized in vernacular photography and more particularly in the experience of the war by the population through photography. In 2006, in the pre-Olympic context, there was a craze for contemporary Chinese art and Timothy Prus understood that it was the right time to collect Chinese photography. As I spoke Chinese and knew the photographers, he entrusted me with the mission of acquiring art for their collection. He had identified 90 prints at the Lianzhou Festival and asked me to contact the photographers, negotiate and supervise the acquisition. I had no training in art or in the art market and that’s what they liked. I matched their state of mind which is to think outside the box. I really enjoyed working with them because they do not try to follow any trends. I worked for them for nine years and helped them acquire about 5,500 photos.

When and how did you start collecting for yourself?

With “Archive of Modern Conflict”, I was mainly dealing with contemporary photographers. Little by little, as I was travelling throughout China, I started to visit flea markets and buy vernacular photography – photography taken without any particular intention. My choice was guided by the aim for surprise, I wanted to be surprised, to find something I hadn’t thought of. This is how I started to collect a lot of photo albums, but I quickly explored all the options at antique markets and so I turned to the Internet. I started to buy a lot on these websites, especially analogue photography.

How did you get from “Archive of Modern Conflict” to “Beijing Silvermine”?

I stopped working for “Archive of Modern Conflict” in 2014. “Beijing Silvermine” was born from a thought I made to myself one day: I collected a lot of analogue photography for myself and for “Archive of Modern Conflict” but I never saw the negatives. So, I started looking for these negatives. This is how in 2009 in Beijing I met a person working in a recycling area for waste containing silver nitrate, including negatives. This was the starting point of the “Beijing Silvermine” adventure.

How do you work with these negatives?

For a long time, the core of the collection was a jumble of everyday life pictures featuring Chinese people posing in China’s most famous places. Much of my work is based on observation. I have been looking at these photos for ten years while remaining attentive to what may emerge from this observation. I then translate this observation by making books, exhibitions and collaborations. This is how the archive can live.

I keep all the negatives that I buy. Sometimes I show an interest in some negatives several years after buying them, for a particular project. At the beginning, I was very selective, I was looking for the real gem. During the first two years of the archive, I deliberately set aside marriage-related images, thinking I would not use them. After all, five years later, I used them for my book « Until death do us part ».

What is your work process to produce a book or an exhibition?

The dynamics between exhibitions and books are not the same. Trough the study of the archive, some themes emerge, and I keep them in mind until making a book. It also allows me to have project ideas to offer when I am invited to participate to an exhibition. For the radish photos I am currently showing in Shenyang, it has been a while since I had this collection of radish photos and was looking at it. When the curator of the exhibition Jérémie Thircuir told me about his exhibition project on the theme of “the farm” at K11, I immediately thought of this series. What is also more and more complicated is the notion of exclusivity and freshness that institutions seek. Some exhibitions require more than a year of work for a show which will only last for a few months. The same goes for books.

How do you select your purchase? Are there some time periods that interest you most?

I don’t have a favorite period, but I let myself guided by a couple of lines. First of all, I’m not looking for collecting what others collect. I have nothing from before 1949. Then, I am guided by the technique. Most of the albums are from 1949 to 1980 and the color negatives from 1985 to 2005, from the introduction of the technique to the arrival of digital. Thus, the limits of the archive are obvious, due to the nature of the photographs that I collect. Finally, I have one last rule, I never buy anything expensive. There is also one last aspect that drives me, which is to buy photos that were just about to disappear, to be destroyed.

I carry on buying, especially on the Internet, at a rate of about 5 to 6 albums per month. I also bought a lot of individual prints and I may have about 1 million negatives purchased in this famous nitrate waste recycling area. Exploiting all these negatives requires a considerable effort. I work with a full-time person to scan the negatives.

Are there many other collectors of Chinese vernacular photography?

There are more and more fairly active Chinese collectors, but we don’t collect the same thing. As they have a particular connection with the history, they mainly seek photographs dating from before 1900.

Do you notice a difference in the reception of your work between the Chinese audience and the Western audience?

Whether Chinese or Western people, I have sometimes encountered persons who do not understand the possibility of exhibiting pictures of anonymous people without permission. But in general, the project has a good reception, for different reasons. Outside of China, it is well received because the archive depicts a portrait of China which is very different from the clichés that we generally have. It shows a face of China that people are not used to see and gives a historical overview of Beijing from the 1980s and 90s. There is also a universal dimension which contributes to the success of the archive. We are no longer just talking about China and Chinese people, but I address topics such as memories, family and loved ones. I realized this universal scope when I showed this project for the first time in Europe during the Format festival in Derby in 2012/2013. I had unexpected reactions from visitors who said they recognized themselves in the photographs taken.

Chinese people are often surprised to see that the history of China can be written only with testimonies and images from everyday people. At first, when I told my Chinese friends about the project, they didn’t see the point. They said they had the same images at home and did not see their artistic value because they were taken by amateurs, nor their historical value because they were taken too close in time.

Besides its artistic dimension, « Beijing Silvermine » also has a sociological value which has interested a couple of researchers. Could you tell us about these collaborations?

Indeed, the archive has lead to collaborations – with sociologists, researchers, PhD students… There are two of them that I find particularly interesting: a collaboration with the Beijing University of Sociology, and another one for a web documentary for France Culture.

The first project, led by Beijing-based French urban planner Jérémie Descamps, was a reflection on the issue of mobility. I made an album bringing together 82 photos of all types on this theme – propaganda images, studio, author and amateur photographs, historical and contemporary images – which served as an interview tool for sociologists. They used the power of the image to touch the interviewees’ feelings, asking them to select and tell about the evocation of 6 images.

The documentary for France Culture, also in collaboration with the urban planner Jérémie Descamps, focuses on the evolution of the city of Beijing between 1992 and today, by comparing an archive image with its contemporary counterpart.

And you, how do you position yourself in relation to the archive?

What is interesting for me is to have this position between distance and proximity. I have the distant gaze of a foreigner on another culture, and at the same time, a certain physical proximity as I lived in Beijing when I started this project, city in which the majority of the “Beijing Silvermine” photos were taken. I was also curious to discover what the city of Beijing was like before I arrived there through the photographs I found. I only work with private, anonymous photos, which only deal with a personal story and narration. But within this immense archive, they no longer only tell a personal story but move to the collective memory, thanks to transversal themes. There is a dimension of voyeurism with the fact of only working with found photos. But there is also the possibility of adopting ethical positions in the way of using these images.

Do you consider yourself an artist?

Yes, indeed. I consider that I wear two hats: the collector’s hat when it comes to collecting photos, and the artist’s hat when it comes to producing something from the photos. However, I don’t consider myself a photographer or an editor.

Can you tell us about your activity as a curator?

To a smaller extent, I also wear the curator’s hat. I can especially mention the work I did with Feng Li, from Chengdu. I discovered his work during the Canton Biennial of photography in 2005. We then stayed in touch thanks to “Archive of Modern Conflict”, acquiring some of his work. In 2016, I decided to organize an exhibition of his work in Paris because it was unknown in France despite being well-renowned in China. He then won the Jimei x Arles festival Discovery Award and I exhibited his work in Arles the following year.

What future do you envision for « Beijing Silvermine »?

The ideal outcome of this project would be for the entire collection to be acquired by a national museum or an institution in China.

What are your future projects?

I am currently presenting a selection of radish photographs as part of “The Farm” exhibition at K11 in Shenyang.

I have also just released a set of prints “Pig” by Feng Li.

Interview by Camille Despré and Lou Anmella-de Montalembert – Paris, December 2019