YAN PEI-MING

Né en 1960 à Shanghai. Diplomé des Beaux-Arts de Dijion en 1986. Vit et travaille entre Dijon et Ivry-sur-Seine

Born in Shanghai in 1948. Graduated from Dijon School of Fine Arts in 1986. Currently lives and works between Dijon and Ivry-sur-Seine.

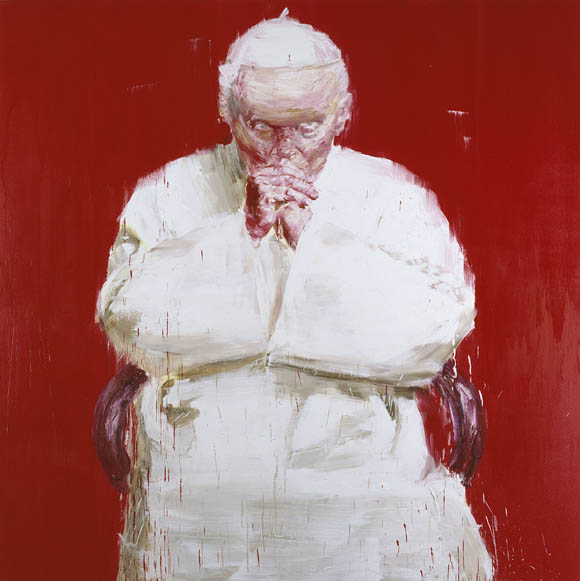

Un tableau de Yan Pei-Ming se reconnaît aisément par ses grandes dimensions, ses propriétés bichromes (noir et blanc, ou rouge et blanc), sa facture épaisse, large et tourmentée, et la gravité de son sujet, religieux, politique ou autobiographique.

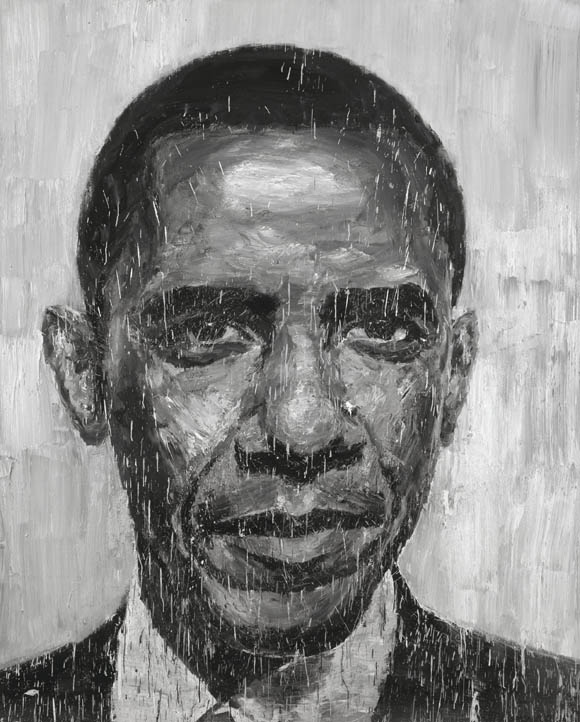

Le portrait de Mao Zedong, décliné au fil des ans en grisaille et en très grand format, constitue l’un des ensembles les plus célèbres de l’artiste chinois installé à Dijon depuis 1980. Ici, les traits se dissolvent dans la matière et dévoilent la personnalité tout à la fois crainte et révérée par le peuple chinois, devenue pour le peintre emblème du père spirituel et du pays déserté. Lorsqu’il peint les portraits de personnalités politiques (Barack Obama, Muammar al-Khadafi mort), ceux de 108 brigands anonymes (Blois, 2008) ou d’une trentaine de nouveaux-nés chinois (Pékin, UCCA, 2009), l’artiste revendique l’autonomie de ses visages et réaffirme sa quête du portrait universel, soucieux de révéler la vérité des peuples par le biais de l’art.

Ce grand amateur de Goya, auquel il a souvent rendu hommage (Exécution, Après Goya, 2008), tend enfin à s’inscrire dans cette tradition historique et artistique, intégrant des fragments de son histoire personnelle lorsqu’il se représente par exemple ainsi que son père, sans vie, dans un polyptique qui répond à la plus illustre des peintures occidentales (Les Funérailles de Monna Lisa, Paris, Louvre, 2005). Une œuvre saisissante, livrée sans détour ni artifice, démontrant toute la puissance évocatrice et émotionnelle de la peinture.

Yan Pei-Ming convoque l’histoire récente à travers l’observation des images médiatiques. Leur transcription à l’échelle monumentale par le médium de la peinture à l’huile confère à l’actualité une dimension historique. Le spectateur est confronté à l’immédiateté d’images au fort potentiel historique mais l’absence de recul temporel crée l’interrogation, le doute et l’émotion.

« C’est à Manet, c’est à Goya que je pense encore une fois devant ces œuvres de Yan Pei-Ming ; à eux avant tous les autres, pour le rappel incessant des désastres de la guerre, le noir et le blanc, la dévotion à la peinture. (…) à la suite de Marat, effondré sur le linge blanc de sa baignoire, le cortège des exécutés et des assassinés, Saddam Hussein, Lee Harvey Oswald, John et Robert Kennedy, Gandhi, Che Guevara, Aldo Moro, Martin Luther King, les bons comme les mauvais, à la morgue, troués, dénudés, étiquetés. Toujours la même histoire, nous dit Yan Pei-Ming. Encore faut-il qu’elle ait ses hérauts, qu’il y ait quelqu’un de taille pour la convoquer, la fixer et la dénoncer, avec cette arme depuis longtemps éprouvée, la peinture. »

Henri Loyrette, pour la préface du catalogue de l’exposition Help! à la galerie Thaddaeus Ropac.

Sources : Slash & Cécile Godefroy pour Arte creative

Yan Pei-Ming is one of the most important figures in contemporary art. He has been focusing on creating large-scale, monochrome paintings, mostly portraits. His works are the vivid result of the passionate, dynamic, and powerful gestures with which he « attacks » the canvas—without lacking in conceptual depth.

He experienced and survived the dramatic changes global geopolitics have undergone since the end of the Cold War. But this generation has also significantly contributed to the reshaping of the globalization process. Struggle, both physical and spiritual, is always central to his creative activities. His paintings are literally the results of intense actions rather than frozen structures of colors and forms. They are in constant agitation, with large and fast strokes. However, they are by no means simply expressionistic, extravagant, and self-indulgent manifestations. Instead, they are always highly « economical » —black and white, occasionally red and white, are the only colors that he employs in creating a universe beyond the « reality » of real color. He constructs his own realm of existence, navigating between memory and humanist concerns. Naturally, with his own particular history, iconic images of historical figures that have exerted profound influences on him and his contemporaries such as Mao Zedong, the Pope, etc. are regularly depicted in his paintings. They are not only images that have marked his memory of public spaces dominated by the propaganda of Maoism and other ideologies; they are also key elements constituting his intimate and personal memory and imagination. This is why Mao’s portraits are often produced and presented side by side with the images of Ming’s own father, his friends, and other, imaginary figures.

Ming’s questioning of the ideal of beauty is deeply related to the question of the fate of humanity, namely the question of how working with images can deeply affect how we perceive and understand life and death, reality and drama, joy and pain, etc. Over the last several years, he has extended his research and representation in a new direction involving a direct engagement with social and geopolitical conflicts and their consequences. Portraits of children from the Third World suffering under the effects of war, starvation, poverty, and other disasters, for instance his paper work Sudanese Child (2006), are shown side by side with those of the Secretaries General of the UN, as well as soldiers involved in the Iraq War.

Over the last few years, he has experimented with new strategies to integrate his studio-produced paintings into public space. His work increasingly ventures beyond the conventional museum space and is installed in public spaces in the form of flags, posters, and so on in order to mobilize public opinion and social awareness. This provocation not only subverts the convention of artistic representation; more importantly, it challenges the common sense of values in public language and established socio-psychological structures, namely the very relationship between freedom of imagination, representation, and social conventions that are systematically conservative. Ming’s work is surely politically engaging. This renders it not only more exciting, but also increasingly relevant in our time of massive change.

Source : Deutsche Bank Collection

TRAVAUX/WORKS :