(English version below)

À précisément minuit à Hong Kong et dix-huit heures au Cap, la curatrice Lemeeze Davids et moi-même avons enfin réussi à nous joindre. Une conversation tant attendue sur la convergence entre la scène artistique africaine et asiatique a eu lieu, après deux semaines de (re)planification. Nos emplois du temps se sont finalement alignés pour laisser place à une discussion passionnée sur les jeunes artistes, la théorie et pratique curatoriale, l’identité, et le pouvoir que nous pouvons tirer de la mémoire et des archives personnelles.

Lemeeze Davids est une jeune curatrice basée au Cap, Afrique du Sud, et à Londres, Angleterre. Son travail se concentre sur l’accessibilité dans l’art et la création d’expériences multisensorielles engageant des publics divers. Fascinée par la manière dont ce processus peut contourner certaines structures et systèmes de pouvoir, elle a partagé ses réflexions sur le travail de jeunes artistes afro-asiatiques et leurs préoccupations, ainsi que sur ses propres recherches et expériences dans le monde de l’art. Lemeeze fut associée à blank projects avant d’être ‘Curatorial Fellow’ à New Curators, soit membre de la première promotion de ce programme dont le but est de former une nouvelle génération de jeunes commissaires d’exposition; où nous nous sommes rencontrées.

ACA project : Plongeons dans le vif du sujet ! J’aimerais en savoir plus sur tes artistes asiatiques préférés en Afrique du Sud, ou inversement, artistes sud-africains en Chine ou en Asie ?

Lemeeze Davids : Absolument ! Mais avant de parler d’artistes contemporain.e.s, je voulais juste mentionner un moment que j’ai vécu en 2018 lors de mes recherches. J’étais au Social History Resource Centre au Cap, une vaste archive d’artefacts de la période coloniale. Elle possède une collection massive de céramiques, de meubles, de textiles, etc. J’étais là, en train de faire une visite guidée avec un membre du personnel, et on m’a montré une collection de fragments de céramiques chinoises datant de la dynastie Han (206 av. J.-C. – 220 apr. J.-C.). Elle m’a expliqué que cela prouvait l’existence d’un réseau d’échange bien établi entre l’Asie et -non seulement le nord mais aussi- l’Afrique du Sud. Ce qui précédait de beaucoup le premier contact avec les Européens. Pour moi, cela a mis en lumière la connexion entre ces deux continents au sein de ma propre identité, et à une échelle mondiale, totalement en dehors du canon eurocentrique.

Je pense toujours à cette connexion afro-asiatique, en particulier avec certain.e.s de mes ami.e.s artistes. Iels explorent cette intersection d’identités entre continents. Je pense à Tzung-Hui Lauren Lee. Elle est une artiste sino-sud-africaine de deuxième génération et se penche sur l’encre sumi et sa matérialité : comment cette encre est fabriquée, le fait qu’elle soit composée de suie, de fumée et de colle animale. La manière dont ce processus documente un certain temps et espace dans la production de cette substance. C’est un procédé qui incorpore ces notions et les absorbe à l’intérieur d’elle-même. Mon autre amie, YunYoung Ahn, est une artiste et designeuse coréenne qui a grandi au Kenya, maintenant basée en Afrique du Sud. Elle se concentre sur l’alimentation et son parcours migratoire intergénérationnel, ainsi que ses profils de saveurs distincts et persistants malgré un effacement historique colonial/impérial. En lisant les recherches artistiques de YunYoung, une citation de Toni Morrison qu’elle mentionne m’a marquée : « Quelqu’un dit que vous n’avez pas de langage, et vous passez vingt ans à prouver que vous en avez un. Quelqu’un dit que votre tête n’est pas bien formée, alors vous recrutez des scientifiques pour prouver le contraire. Quelqu’un dit que vous n’avez aucun art, alors vous labourez pour le ressortir. … Rien de tout cela n’est nécessaire. »

Une de mes meilleures amies, Shelley Pryde, une théoricienne queer et Drag King qui vivait à Shanghai, m’a indirectement inspirée à apprendre le mandarin. Grâce à cela, j’ai pu me connecter avec une communauté taïwanaise au Cap. Je lui ai demandé si elle connaissait des artistes africain.e.s vivant en Asie, car je n’en connaissais pas. Et il s’avère que ce n’est pas très courant. Je trouve que cette connexion afro-asiatique, imprécise, est vraiment productive et mérite d’être démêlée et re-mêlée un peu plus – mais jamais définie. L’article de Joan Kee dans October, « Why AfroAsia? », met en avant certaines de ces interactions artistiques entre le Nigeria et la Chine, le Zimbabwe et la Corée, etc., qui remettent directement en question la façon dont l’Histoire de l’Art a été établie.

Il y a aussi Senga Nengudi, qui a déménagé au Japon. Elle fut attirée par le mouvement d’art Gutai, ce qui a engendré des connexions incroyables. Un autre exemple, lorsque je travaillais chez blank projects, fut ma collaboration avec Sabelo Mlangeni. Il faisait partie d’une exposition collective à Para Site, Hong Kong (« While we are embattled« , 2022). J’étais vraiment contente pour lui, de voir son travail examiné dans ce contexte. C’est important d’avoir ce dialogue.

Très bon point. Parmi toutes les expositions que j’ai vues à Hong Kong, il n’y a pas eu beaucoup d’artistes africain.e.s. Plutôt des artistes afro-américain.e.s et caribéen.ne.s. Il y a tellement à faire, avec tant de connexions intéressantes. Par exemple, j’effectue des recherches sur Hong Kong en tant que ville portuaire et le Cap est aussi une ville portuaire ! Dis-moi, si tu pouvais monter une exposition connectant l’Asie et l’Afrique, ou l’Afrique du Sud et un pays en Asie, quels liens penserais-tu explorer ?

Je pense qu’organiser une exposition sur l’Asie et l’Afrique est un très gros projet. Il y avait une exposition appelée « Indigo Waves » présentée dans diverses institutions entre Le Cap et Berlin en 2023, organisée par Natasha Ginwala et Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung. Elle se concentrait sur l’océan Indien comme point d’ancrage, en étudiant comment les peuples d’Asie du Sud et d’Afrique de l’Est l’utilisaient comme source de vie et comment cela les connectait. Si je devais monter une exposition liant ces deux continents, similaire à « Indigo Waves », je me concentrerais sur un élément qui les relie. Par exemple, le fait qu’Hong Kong et le Cap soient toutes deux des villes portuaires est une connexion fascinante.

Je veux revenir sur quelque chose que tu as mentionné avant. Tu parlais de la manière dont Tzung-Hui Lauren Lee et YunYoung Ahn abordent leur identité à travers leur art. Je me demandais si tu utilises également la curation comme moyen pour mieux comprendre ton histoire, ou si tu traces une ligne bien définie entre tes recherches personnelles et ton travail ?

Je pense que mon véritable travail est de me comprendre moi-même, et le monde qui m’entoure. Les choses sont plus simples lorsqu’on a un intérêt personnel dans ce que l’on fait. Ça peut sembler évident, mais je crois que ça ajoute une étincelle – et le travail d’un.e curateur.ice, au final, c’est de se soucier des choses qui nous entourent, c’est l’idée du ‘care’ ou du ‘prendre-soin-de’. De plus, il ne m’est pas difficile de m’intéresser à… tout ! Une fois, j’ai écrit tout un essai sur l’origine de la couleur pourpre. J’étais troublée que son association avec la royauté provienne du fait qu’elle fut produite à partir de sang fermenté de milliers d’escargots de mer récoltés en Afrique du Nord.

Je décortiquais toutes ces informations en tant qu’artiste, mais j’ai fini par m’orienter vers le commissariat d’exposition et la recherche archivistique. J’étais étudiante en art, je comprends pourquoi mes ami.e.s s’intéressent à leur identité à travers leur pratique. Mais approchant de la fin de mon diplôme, j’ai remarqué un assez fort changement où je me suis vraiment passionnée pour la curation et ce que cette pratique pouvait apporter aux artistes – ainsi qu’à moi-même en tant que personne qui aime déceler des connexions qui ne sont à priori pas apparentes. Mais j’essaie de ne pas imposer mes centres d’intérêts dans un projet. Donc, je ne dirais pas que j’utilise la curation comme un outil pour explorer mon identité. J’aime plutôt travailler avec des artistes qui sont sur la même longueur d’onde que moi, qui offrent des conversations intéressantes et remettent en question ma façon de penser. Cela a été vraiment enrichissant, comparé à la création artistique où je me sentais parfois dans une sorte de bunker avec moi-même.

Tu parles de ce changement dans ta pratique, cette transition : y a-t-il quelque chose de spécifique qui a fait basculé ta pratique ?

Oui, le département dans lequel j’étudiais proposait de la photographie, de la gravure, de la peinture, du dessin… Et je passais beaucoup de temps à glisser d’une discipline à l’autre. Je voulais tout faire tout le temps. Le produit final était donc une installation multidisciplinaire dont j’arrangeais constamment les éléments, et dont j’explorais les connexions. C’est à ce moment-là, lorsque j’étais tellement absorbée par l’organisation de l’installation – plus que par sa création en elle-même – que j’ai réalisé que je n’avais pas forcément besoin de fabriquer les objets en question. Je voulais plutôt explorer, rechercher et analyser. C’était stimulant pour moi de contempler les œuvres des autres et les relier à mes propres réflexions. J’ai vu la curation comme une grande installation où la recherche et des œuvres externes devenaient mon médium en quelque sorte.

Tu m’avais dit quelque chose qui m’a vraiment marquée. C’est une phrase que je reprends quand on me demande pourquoi j’ai mis ma pratique artistique en pause. Tu m’as dit que tu avais plus à dire en tant que curatrice qu’en tant qu’artiste.

Oui ! Je me souviens qu’une fois on m’a demandé si je n’allais pas ressentir de la jalousie en travaillant avec des artistes, puisque ce n’était pas moi qui créais l’œuvre en question. J’ai été tellement surprise par cette question. Non, parce que ma pratique ne provient pas de la jalousie. Elle découle de ce besoin de faire communauté. Et au fond, bien sûr, je serai toujours artiste. Je penserai toujours de manière artistique. Comme toi, nous continuerons toujours à créer de l’art d’une façon ou d’une autre – que cela se retrouve dans une exposition ou non, dans notre studio, ou même si cela ne finira jamais par voir le jour ; ce n’est pas le sujet. Comme tu l’as dit, j’ai plus à dire en tant que curatrice, et toute mon énergie est focalisée sur la création d’expositions et sur le fait de générer des connexions intéressantes dans ce monde.

On a beaucoup parlé d’expériences sensorielles lors de notre discussion. Je me demandais comment cet intérêt t’es parvenu et pourquoi ?

C’est venu d’une insatisfaction vis-à-vis du modèle du “white cube” que j’ai rencontré en tant que jeune artiste. Avec ma pratique interdisciplinaire, je sentais que la manière dont l’œuvre était examinée dans un espace aseptisé, cette obsession moderniste d’isoler les œuvres d’art, étaient assez problématiques. Je sentais que cela enlevait une partie du contexte dans lequel je voulais que mon travail soit interprété. Je voulais aussi explorer mon héritage, dont je savais qu’il avait des racines en Chine, au Yémen, en Indonésie et/ou en Malaisie, et/ou dans les populations autochtones d’Afrique du Sud. Les « et/ou » venaient du manque de connaissances concrètes et de documentation sur les ancêtres des personnes réduites en esclavage, par les régimes coloniaux britanniques et néerlandais dans l’histoire de l’Afrique du Sud. La « documentation » dont je disposais provenait en fait de formes de connaissances moins reconnues : récits oraux, recettes, langages, odeurs. J’ai réalisé que même si je ne pouvais jamais résoudre ces « et/ou », je pouvais embrasser cette ambiguïté – il me suffisait de trouver les outils pour le faire. Lorsqu’il s’agit de parler de ces histoires complexes et chargées, je pense qu’il est inefficace de définir ou de mettre une étiquette sur quelque chose – à savoir essayer de présenter une information dans une case bien définie. Pour faire une exposition postcoloniale, il faut pouvoir résister à l’archivage et accueillir cette ambiguïté. Autant j’ai travaillé avec des archives, autant il est nécessaire de défier l’héritage des cabinets de curiosités, et redéfinir ce qu’est un musée. Le sensoriel est venu lorsque je me suis penchée sur cela et que j’ai réfléchi à comment bien documenter quelque chose. Ça m’a conduit à la nourriture, et aux relations que nous construisons autour d’elle.

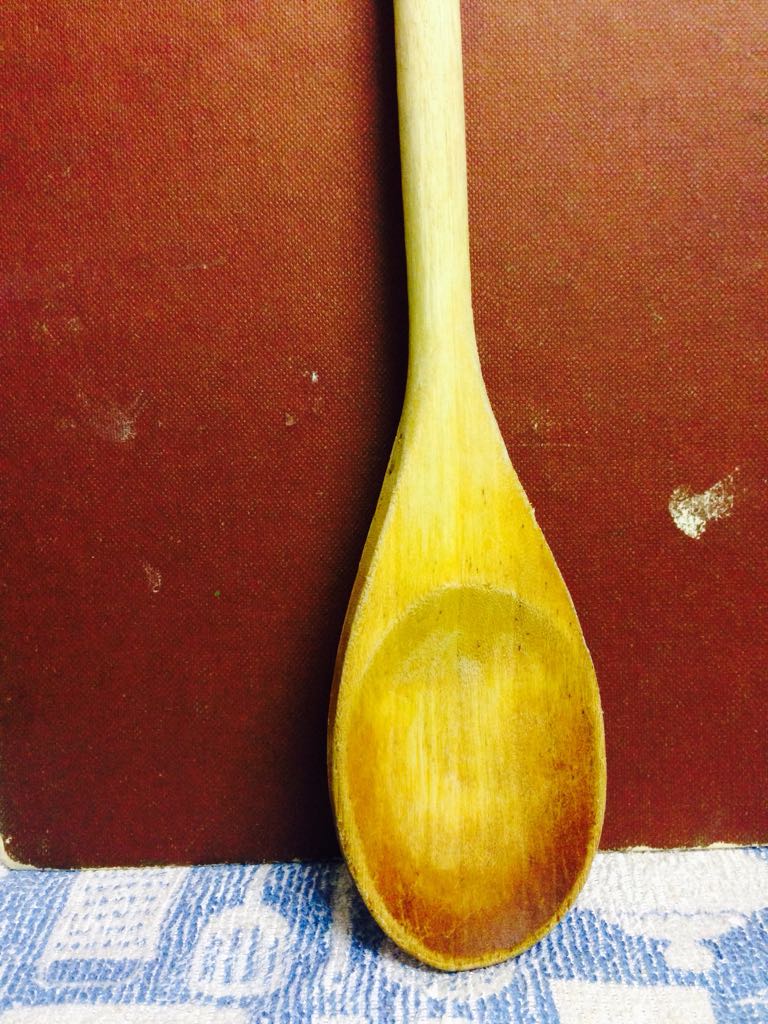

En lien avec ce que tu viens de partager, tu as écrit un article sur les taches de nourriture comme ‘archives accidentelles’ en te concentrant sur la cuillère en bois de ta grand-mère – un texte que j’ai beaucoup apprécié d’ailleurs. Pourrais-tu nous en dire un peu plus sur la manière dont tu t’es inspirée de cet intime détail et comment cela se rapporte à ta pratique curatoriale ?

C’est parti d’une étude d’objet qui défendait l’idée que cette cuillère en bois était une sorte d’«archive accidentelle». J’ai hérité de cet ustensile d’un.e membre de ma famille. Elle était déjà avec nous depuis 2 générations. Elle a un bord brûlé, raboté, et fait preuve de témoignage de ma vie ainsi que de tous les repas qui m’ont précédée. C’est un objet qui épouse et absorbe la main du.de la cuisinier.ère et s’y adapte, il porte les strates d’épices qui documentent tous les plats qui ont été préparés. Cela reflète les circonstances économiques de la personne qui cuisinait, ses recettes préférées, les épices accessibles et donc le commerce des épices qui a touché notre histoire, soit l’histoire coloniale, et bien plus encore. C’est une accumulation de toutes les manières dont vous avez pu subvenir à vos besoins alimentaires, c’est une partie de votre vie. C’est pour moi une archive parfaite, car elle ne porte pas la violence de la conservation, elle s’approche plutôt de quelque chose qui est collecté par la nature même du fait de vivre.

En tant que curatrice qui prône fortement l’expérience immatérielle, je pense que c’est un important exercice que de se plonger dans l’histoire des objets; en orientant ma pratique curatoriale vers des questions telles que : que signifie préserver et communiquer quelque chose qui n’est pas complètement déchiffrable ? Pourquoi la cuillère en bois, la cuisine, et les recettes fonctionnent-elles si bien comme métaphores pour négocier mon identité et celle des autres ? Comment le fait de partager un repas avec quelqu’un peut-il créer un temps et espace spécifique ? Comment puis-je résister aux archives, tout en épousant le désir d’un passé connu ?

Je trouve ce projet vraiment spécial. Y a-t-il des artistes dont la pratique interagit avec les archives d’une manière qui t’intrigue ?

J’étais à la Biennale de Venise cette année et j’ai été ravie de voir Odorama Cities de Koo Jeong A au pavillon coréen – son travail s’intéresse à la mémoire et à la cartographie en utilisant l’odeur comme outil cartographique. Je crois que l’objectif était de dresser un portrait de la péninsule coréenne – et c’est exactement ce sur quoi porte ma recherche : l’olfaction, le sens de l’espace, travailler ensemble… Les odeurs recueillies comprenaient des notes telles que « escalier en bois », « kaki », « filets de pêche abandonnés », « l’odeur du savon de ma mère », etc. J’ai trouvé que c’était un projet vraiment spécial et un exercice intéressant sur la manière d’inclure les odeurs dans une exposition.

Zayaan Khan est une autre artiste dont j’apprécie beaucoup le travail. Elle a créé une Seed Biblioteek ou bibliothèque de semences, qu’elle utilise pour partager des connaissances sur la nourriture et la fermentation. Les gens sont invités à « emprunter » des graines à la bibliothèque et à les rendre à la saison suivante !

J’adore le fait que, même lorsque tu parles d’archives, c’est une expérience sensorielle qui transparaît. Ce qui vient à questionner ce qu’est -ou pourrait être- une archive. Je me demande alors quel rôle les archives peuvent jouer dans l’art selon toi ?

Nous avons déjà abordé quelques points, mais je pense que le rôle de l’archive est quelque chose qui a été vraiment prévalent tout au long de ma pratique curatoriale.

Bien que je me considère comme quelqu’un de très anti-objet – et je ne suis pas tout à fait sûre de ce que cela signifie – j’aime beaucoup les expériences comme celles que j’ai mentionnées auparavant, soit les œuvres d’art éphémères, les performances, les installations multimédia, etc… Je suis toujours une grande adepte de l’utilisation des archives et du recours au passé pour produire de nouvelles connaissances.

Il y a aussi la pratique de la création de sa propre archive, comme le fait Zayaan. C’est l’idée que nous pouvons produire quelque chose de complètement nouveau, mais qui s’inspire de ce qui s’est écoulé avant nous. Il faut remonter le temps, le ‘rabattre’ en quelque sorte – c’est ce que fait une archive. C’est ramener le passé au présent et le faire avancer vers l’avenir. Il s’agit de tordre le temps et le cumuler jusqu’à un seul moment, celui de la recherche. C’est ce qui, à mon avis, est vraiment puissant avec le travail autour des archives.

Entretien mené par Amandine Vabre-Chau – Octobre 2024

It was midnight in Hong Kong and 6 pm in Cape Town when curator Lemeeze Davids and I finally managed to catch each other. A long overdue conversation on the convergence between the African and Asian art scene took place after two weeks of planning. Our schedules eventually aligned to make place for a passionate discussion on captivating young artists, curation, identity and the political power of personal memories and archives.

Lemeeze Davids is a young curator based in Cape Town (South Africa) and London (UK). Her work focuses on making art accessible, and creating multi-sensory experiences that engages diverse audiences. Fascinated by how this process can bypass certain power structures and value systems, she shared her thoughts on Asian-African artists and their concerns as well as her own research and experience. Lemeeze was associate at blank projects before becoming a curatorial fellow at New Curators, where we both met.

ACA project : Let’s jump straight into it! I’d love to know more about your favourite Asian artists based in South-Africa, or, conversely, South-African artists based in China or Asia?

Lemeeze Davids: For sure! But before I speak about contemporary artists, I just wanted to mention this moment I had in 2018 when I was conducting an archival object study. I was at the Social History Resource Centre in Cape Town, this sprawling archive of artefacts from the colonial period. It’s got a massive collection of ceramics, furniture, textiles etc… I was there getting a tour from one of the staff members and was shown a collection of Chinese ceramics shards that dated back to the Han dynasty, which is about 200 BC (206 BC–AD 220). She detailed that this gave evidence that there was a well-established trade network between Asia and -not only the northern part but- Southern Africa. This pre-dated the first contact Europeans had by a large, large, amount of time. I think for me it highlighted the connection between the two continents within my own identity and on this global scale – existing totally outside of this Eurocentric canon.

I’m always thinking about this Afro-Asian connection, especially when it comes to some of my artist friends. Some of whom unpack this intersection of identity of continents. I’m thinking of Tzung-Hui Lauren Lee. She’s a second generation South African Chinese artist and she looks at sumi ink as material: how it’s made, the fact that it’s composed of soot- smoke, and animal glue. How it’s a process that documents time and space, that ‘folds’ it. My other artist friend, YunYoung Ahn is a Korean artist and designer who was raised in Kenya, but based in South Africa now. She focuses on tracing intergenerational foodways and flavour profiles in spite of colonial/imperial history. Reading through YunYoung’s artistic research, one quote by Toni Morrison that she brings up goes: “Somebody says you have no language, and you spend twenty years proving that you do. Somebody says your head isn’t shaped properly so you have scientist working on the fact that it is. Somebody says you have no art, so you dredge that up. … None of this is necessary.”

It was actually one of my best friends, Shelley Pryde, a queer theorist and Drag King, who was living in Shanghai, who indirectly inspired me to begin learning Mandarin. Through that, I was able to connect with a Taiwanese community in Cape Town. I had a conversation with her about whether she knew of any African artists living in Asia because I actually don’t know any of those. And turns out it actually wasn’t very common. I find the imprecise AfroAsian connection something really productive, one that needs to untangled, re-tangled, detangled a little bit more – but never defined. Joan Kee’s article in October, ‘Why AfroAsia?’ highlighted some of these artistic engagements between Nigeria and China, Zimbabwe and Korea, etc… that directly challenge what Art History has come to be known as.

There’s also Senga Nengudi who moved to Japan, she was really drawn to the Gutai art movement and that did foster incredible connections. There was one example when I worked at blank projects, I was working with Sabelo Mlangeni and he was part of a group show at Para Site in Hong Kong (While we are embattled, 2022). I was really excited about that for him, having his work being spoken about in this context. It’s important to have that dialogue.

Great point. From all the exhibitions I’ve seen in Hong Kong there haven’t been that many African artists. Some African-Americans and Caribbean artists mostly. There is so much to do, there are many interesting connections. I’m doing research on Hong Kong as a port-city for example and Cape Town is a port-city ! Tell me, if you were able to make an exhibition connecting Asia and Africa, or South Africa and a specific country in Asia, what links do you think you’d explore?

I think making a show about Asia and Africa is a massive endeavour. There was a show called Indigo Waves that was hosted in various institutions between Cape Town and Berlin curated by Natasha Ginwala and Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung. It looked at the Indian Ocean as an anchoring point, studying how people from South Asia and East Africa used it as a life source and how that connected them. If I had to curate a show with that, similar to Indigo Waves, I would focus on one thing that connects both continents. For example, Cape Town and Hong Kong being port-cities, that is a fascinating connection.

I’m going to jump back on something you said before. You talked about how Tzung-Hui Lauren Lee and YunYoung Ahn look at their identity through their art. I was wondering whether you also use curation as a way to better understand your background, or if you draw a firm line between your personal inquiries and your work?

I think my true work is to understand myself and the world around me. It makes things easier to have a personal interest in what you are doing. It might be an obvious thing to say, but I believe it adds a spark – and a curator’s job at the end of the day is to care. I also don’t think it’s difficult to have an interest in… whatever! I once wrote an entire essay on the origin of the colour purple because it confounded me that its association with royalty came from the fact that it was produced from the fermented blood of thousands of sea snails harvested in North Africa.

I was once processing all this information as an artist but switched to exhibition-making and archival research. I studied art and understand why my friends delve into their identity through their practice. I just found this distinct shift towards the end of my degree where I became really engrossed in curating and what that offered artists- and myself, as someone who likes researching and teasing out connections. But I try not to bring my research interests into a project where it’s overbearing. So I wouldn’t say I use curating as a tool to work through my own identity. Rather I enjoy working with artists who are on the same page as me, who provide really interesting conversations and challenge my way of thinking. It’s been really rewarding, as opposed to making art where I felt like I was in a bit of an echo chamber with myself.

You talk about this shift, was there something very specific that made you change practices?

Yeah the department I was studying in had photography, printmaking, painting, drawing… And I would switch a lot between all these. I think I struggled to find a major because I just wanted to do everything all the time. What I eventually produced was a multidisciplinary installation work where I found myself arranging things and looking at the connection between these objects. It was that moment, when I was so engrossed with the organising of the installation -more so than the actual making of it- that I realised I don’t necessarily need to make the items. I wanted to tease out, research and look more closely instead. And it felt exciting for me to look at other people’s art and think about it in relation to my own. I saw curating like one big installation where research and external artworks were somewhat my medium.

There’s a sentence that you once said that stuck with me. I actually say that now when people ask me why I pressed pause on my practice as an artist: you said that you had more to say as a curator than as an artist.

Yes, I remember once being asked if I would be jealous working with artists as they would have made the art and not me. I was so taken aback by that question. No, because my practice doesn’t come out of jealousy. It comes out of is this need for community building. And at heart, of course, I will always be an artist and thinking in art-making ways. A lot like you, we will always make art – whether or not that ends up in an exhibition or whether that ends up in our studio, or whether it even ends up being made. Like you said, I have more to say as a curator, and all my energy is just focused on making exhibitions and bringing interesting connections into the world.

When we were chatting together a lot came up about sensorial experiences. I was wondering how that interest first came to you, and why?

It came from a dissatisfaction with the white cube model which I encountered as a young artist. While making interdisciplinary art, I felt the way the work was examined in a sanitised space and this modernist obsession of isolating artworks were problematic. I felt that removed some context within which I wanted the work to be read. I was also interested in exploring my mixed heritage, which I knew had roots in China, Yemen, Indonesia and/or Malaysia, and/or Indigenous South Africa. The “and/or”s came from a lack of concrete knowledge and documentation of ancestry of people forced into slavery by the British & Dutch colonial regimes in South Africa’s history. The ‘documentation’ I had to go from was in fact less recognised forms of knowledge: oral accounts, recipes, language, scents. I began to realise that although I could never remedy the ‘and/or’s, I could embrace the ambiguity – I just needed to find the tools to do so. When talking about these complex and loaded histories, I don’t think defining or putting a label on something- trying to present information in a neat box- is a very efficient process. For postcolonial exhibition making, you need to be able to resist archiving something and embrace this ambiguity. As much as I’ve worked with archives, and looked at archival projects, you need to defy the legacy of the Wunderkammer and what a museum is. The sensorial came because I was leaning into that and thought about how to document something, it led me to food and the relationships we build around it.

Related to what you just said, you wrote a piece on food stains as accidental archives by focusing on your grandmother’s wooden spoon – which I really loved by the way. Could you tell us a bit more about how you drew from such intimate details and how that relates to your own curatorial practice?

That evolved out of an object study which followed the argument that this wooden spoon was something of an ‘accidental archive’. As someone who inherited the spoon from a relative two generations older than me, with a lobbed-off burnt edge, it was not only a testament to my life but to all the meals that came before me. It’s an object that absorbs the cook’s grip and mutates to it, it carries layers of spice staining that document all the food that the cook has made. This pointed to economic circumstances, favourite recipes, accessible spices and the spice trade, colonial histories, and more. It becomes a multi-layer of all the meals you’ve ever eaten and all the ways that you’ve sustained your own life. It’s not only my life that I’m looking at as an archive, but two, three generations worth of lives that that spoon has been passed down to. It is something of a perfect archive for me because it doesn’t hold the violence of keeping, but rather, something that is collected by the nature of living and life.

As a curator who preaches a lot about intangible experience, I think it’s also an important exercise to delve into object histories, directing my curatorial practice to questions such as: what does it mean to record and communicate something that is not completely knowable? Why did the wooden spoon, the kitchen, and the recipe work so well as a metaphor for the negotiation of my own and others’ identities? How can sharing a meal with someone create time, space, and place? How can I resist the archive, while still embracing the desire for a known past?

That’s really special. Are there any artists globally whose practice interacts with archives in a way that intrigues you?

I was at the Venice Biennale this year and really thrilled to catch Koo Jeong A’s Odorama Cities at the Korean pavilion – their work looks at memory and spatial mapping through smells that were housed in different parts of a seemingly empty space. I believe the goal was a portrait of the Korean peninsula – and this is exactly what my research delves into: the olfactory, the sense of space, working together to act as a tool of nuance. The scents they collected included notes like ‘wooden stairs’, ‘persimmon tree’, ’abandoned fishing nets’, ‘the smell of my mother’s soap’ etc. I thought it was a really special project to experience and an interesting exercise in how to include smell in an exhibition.

Another artist whose practice I enjoy spending time with is Zayaan Khan, who created a Seed Biblioteek or Seed Library, which she uses to share knowledge about food, fermentation, and community to resist against the etched systems of colonialism in South Africa. People are welcome to ‘borrow’ seeds from the library and return them in the next season.

I love that even when you talk about archives, it’s still a sensorial experience that comes through. That itself is questioning what an archive is or could be which makes me wonder what you think the role of archives can play in the arts?

We’ve touched on a few points but I think the role of the archive is something that’s been prevalent throughout my curatorial practice. Even though I consider myself someone who’s very anti object- and I’m not entirely sure what that means- I really enjoy experiences and ephemeral artworks (performances, media-based artworks, time based artworks…). I’m still a huge fan of mining the archive and looking at things from the past to produce new knowledge.

There’s also the practice of building your own archive like Zayaan does. It’s this idea that you can produce something completely new but that’s also informed by what has come before you. You almost have to go back in time. You have to fold time together and that’s what archiving does. It brings the past to the present and you are basically taking it forward into the future. It’s about folding time three ways into one flat moment where you’re just researching. That’s what I think is really powerful about it.

Interview by Amandine Vabre-Chau – October 2024

ACA project est une association française dédiée à la promotion de la connaissance de l’art contemporain asiatique, en particulier l’art contemporain chinois, coréen, japonais et d’Asie du sud-est. Grâce à notre réseau de bénévoles et de partenaires, nous publions régulièrement une newsletter, des actualités, des interviews, une base de données, et organisons des événements principalement en ligne et à Paris. Si vous aimez nos articles et nos actions, n’hésitez pas à nous soutenir par un don ou à nous écrire.

ACA project is a French association dedicated to the promotion of the knowledge about Asian contemporary art, in particular Chinese, Korea, Japanese and South-East Asian art. Thanks to our network of volunteers and partners, we publish a bimonthly newsletter, as well as news, interviews and database, and we organise or take part in events mostly online or in Paris, France. If you like our articles and our actions, feel free to support us by making a donation or writing to us.