by Eléonore Dalzon

Sun Mu 선무 s’affranchir des frontières par la création

Si une image vaut mille mots, l’oeuvre de Sun Mu en vaudrait le double. L’artiste nord-coréen, dont le nom d’emprunt signifie « sans frontières », confronte le spectateur à une imagerie déstabilisante ; il faut savoir lire à travers les lignes de ses travaux pour en saisir l’aspect subversif. Sun Mu – dont le visage reste inconnu afin de garantir sa sécurité et celle de ses proches toujours en Corée du Nord – reprend au travers de tableaux, collages, installations, ou plus récemment NFT, les codes artistiques qui lui furent transmis en RPDC, afin d’oeuvrer pour la paix.

Les enfants ont une place particulière dans le corpus de l’artiste. A première vue, l’oeuvre Song of Joy semble enfantine, joyeuse même. Sur un fond rose une petite fille se dessine, elle est vêtue d’un uniforme impeccable, de souliers vernis et ses cheveux sont ornés d’une fleur jaune. Sur ses épaules repose un foulard rouge et sur l’une des bretelles de sa jupe, on peut retrouver un badge, probablement à l’effigie de l’un des leaders de la famille Kim. Il semble que nous ayons à faire à une petite fille nord-coréenne, somme toute normale. De plus, le tableau s’intitule Song of Joy (Chanson joyeuse), mais c’est bien là que se trouve l’ironie de l’oeuvre de Sun Mu. L’enfant paraît heureuse, mais l’est-elle vraiment ? Lorsqu’il nous est donné de découvrir son visage on distingue un sourire exagéré, fabriqué de toutes pièces, une dent manque et ses sourcils sont déformés. Sur le visage de la fillette, un masque grimaçant semble plaqué et derrière celui-ci, se déroule une réalité plus sombre dont l’enfant ne semble pas avoir conscience. Selon Koen de Ceuster le travail de Sun Mu « n’est pas foncièrement anti Nord Coréen mais bien plus nuancé, une mise en abîme où il joue avec l’attraction que peuvent exercer les couleurs primaires et des émotions positives, joyeuses, […] Mais si l’on regarde de plus près, quelque chose cloche et derrière ce bonheur apparent persiste un sentiment profondément dérangeant. » (1)

Sun Mu reçoit sa première formation artistique en Corée du Nord. Après trois années d’études, il devient un artiste au sein de l’armée nord-coréenne lors de son service militaire. Il vante alors avec conviction le régime et ses mérites. Mais la famine qui sévit dans les années 1990 pousse Sun Mu à quitter son pays pour la Chine, il ne réalise pas alors que ce départ est définitif. Selon lui « La Corée du Nord était un bon pays. J’étais l’un de ceux qui souhaitaient mourir pour le leader » (2). Lorsqu’il traverse de nuit la rivière Tumen, il devient de fait apatride. Ne pouvant rentrer dans son pays, il décide de se rendre en Corée du Sud, arrivé là-bas en 2002, il poursuit ses études d’art à la Hongik University.

A Séoul, il met des années à se défaire du spectre des leaders. En arrivant dans la capitale sud-coréenne, il perd ses repères, comprend l’ampleur du mensonge et découvre la liberté de penser et d’expression. Peu à peu, il y trouve sa vocation et se met à exorciser l’emprise des Kim au travers de son art. En se dissociant des Kim, il devient Sun Mu et exerce « sa propre propagande » (3).

Il dresse des portraits satiriques, presque comiques des leaders. Avec ironie, il représente Kim Jong-Un sous les traits d’un Jesus barbu ou n’hésite pas associer les leaders à de grandes franchises américaines, comme Disney ou Coca-Cola. Il va même plus loin dans la caricature et sans détour, il peint Kim Jong-Il, couteau au poing, le visage animé d’un sourire carnassier. Sur les verres des lunettes du dirigeant se reflètent des scènes de labeur et de mise à mort.

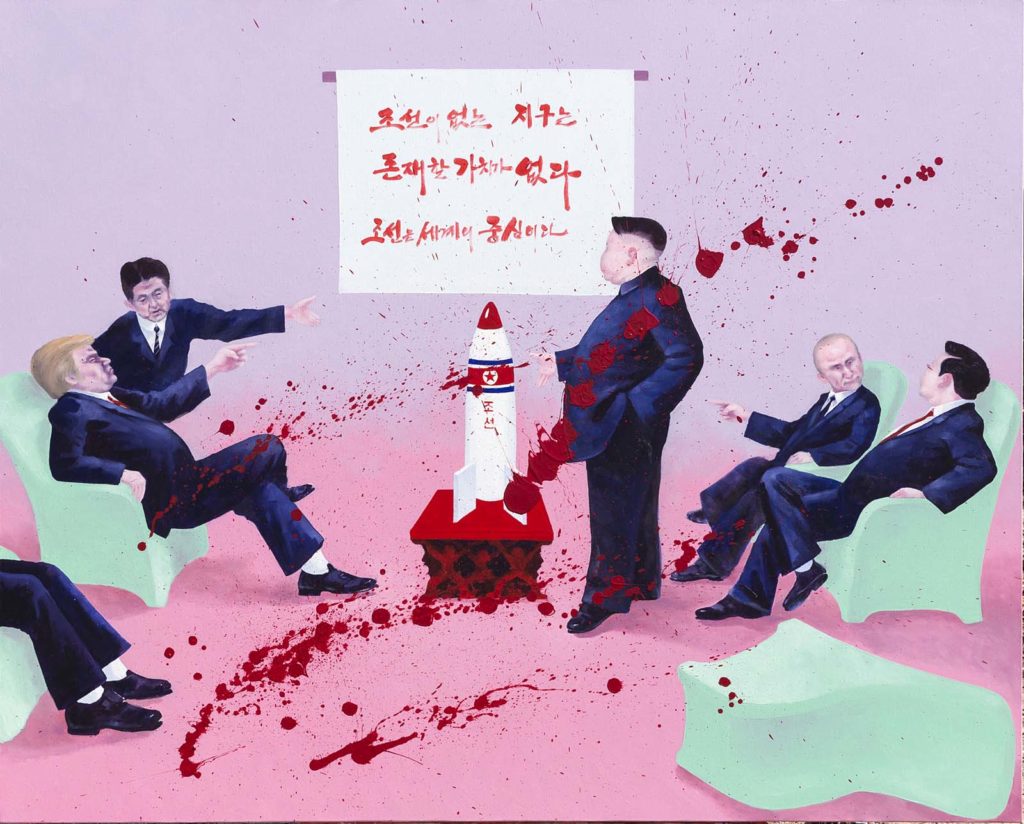

Par ailleurs, Sun Mu ne se contente pas uniquement de pointer de son pinceau le régime nord-coréen et l’illusion dans laquelle il maintient son peuple. Ce sont aussi les Etats-Unis, le Japon, la Russie … toutes ces nations impliquées dans la séparation de la Péninsule et donc directement ou indirectement liées à l’avènement des Kim que le peintre désigne et dénonce dans son oeuvre Leaders, qu’il éclabousse de peinture rouge venant par la même occasion entacher la figure des ces hommes politiques.

Si Sun Mu possède aujourd’hui une renommée internationale, son parcours fut parsemé d’embuche. Il doit par exemple affronter lors de sa première exposition en 2007 l’ignorance des sud-coréens, et la méfiance de la police qui l’interroge, car faire l’apologie du régime des Kim est interdit par la loi au Sud de la Péninsule. C’est en 2014, lorsqu’il retourne en Chine, à Pékin, pour réaliser une exposition personnelle, que l’artiste se heurte directement à la censure. S’il connaît les risques de cette entreprise, il voit son exposition avortée par les autorités chinoises sous la pression du gouvernement nord-coréen. Ayant conscience de la présence inévitable d’agent de la RPDC, Sun Mu avait réalisé à cet effet une peinture de 5 mètres de long où le nom des Kim était écrit. Posée sur le sol à l’entrée de l’espace d’exposition les visiteurs n’auraient eu d’autres choix que de la piétiner et donc de commettre un véritable blasphème. Cette mésaventure est notamment relatée dans le documentaire « I am SunMu » sorti en 2015 (4).

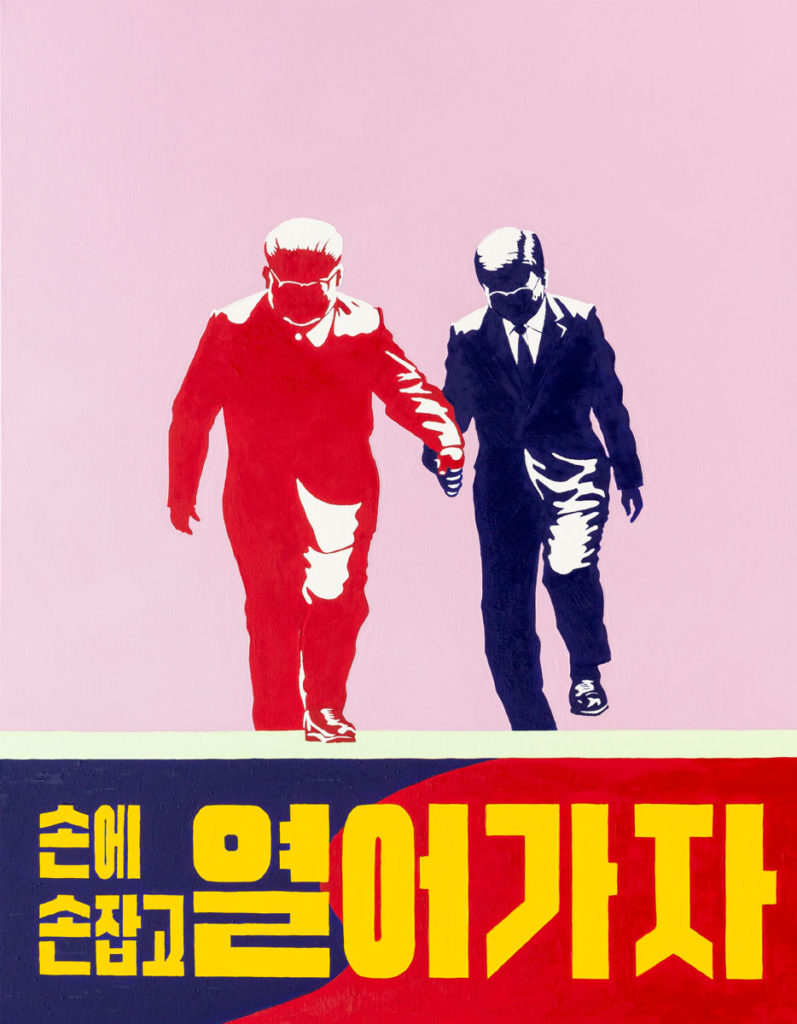

Provocateur et satirique, l’artiste porte à travers de son art un message d’espérance, comme dans la peinture « At Panmunjom » où Kim Jong-un et Moon Jae-in, ensemble, main dans la main, franchissent la frontière entre les deux Corées. Sun Mu travaille à abattre des murs et peint une fresque complexe, au-delà de l’image en Noir et Blanc que l’on peut se faire de la Péninsule. Il s’élève comme la voix d’un peuple que l’on a bâillonné.

Sun Mu 선무 emancipating from frontiers through art

If a picture is worth a thousand words, Sun Mu’s work would be worth twice as much. The north-Korean artist, whose assumed name means « no borders », confronts the viewer with disruptive imagery; you have to be able to read through the lines of his work to grasp its subversive aspect. Sun Mu – whose face remains unknown for his safety and that of his relatives still living in North Korea – uses through paintings, collages, installations and, more recently, NFT, the artistic codes taught to him in the DPRK, to advocate for peace.

Children have a special place in the artist’s body of work. At first glance, the work « Song of Joy » seems childlike, even joyful. On a pink background, a little girl takes shape, dressed in an impeccable uniform and polished shoes, her hair adorned with a yellow ornament. A red scarf rests on her shoulders and on one of the straps of her skirt is a badge, probably bearing the effigy of one of the leaders of the Kim family. We seem to be dealing with a normal little North Korean girl. Furthermore, the painting is entitled « Song of Joy », though it’s in this very title that lies the irony of Sun Mu’s work. The child looks happy, but is she really? When we see her face, we see an exaggerated, fabricated smile, a missing tooth and distorted eyebrows. On the girl’s face, a grimacing mask seems to be plastered, however behind it, the child is unaware of a darker reality unfolding. According to Koen de Ceuster, Sun Mu’s work, “is often not crudely anti North Korea, but rather much more nuanced and multi-layered, where he plays with the appeal of the sugar candy primal colors and the upbeat emotions, […] But on closer scrutiny, something is amiss and under the apparent “happy shiny people” something deeply uncomfortable lingers.” (1)

Sun Mu received his first artistic training in North Korea. After three years studying, he became an artist in the North Korean army during his military service. He praised the regime and its merits with conviction. But the famine of the 1990s forced the artist to leave his country for China, and he did not realized that his departure was definitive. According to him, « North Korea was a good country. I was one of those who wanted to die for the leader » (2). When he crossed the Tumen River at night, he became de facto stateless. Unable to return to his homeland, he decided to reach South Korea. Arriving in 2002, he then decided to pursue his art studies at Hongik University.

In Seoul, it takes him years to become undone with the leaders’ specter. When he arrived in the South Korean capital, he was disoriented, he realized the extent of the lie he was living in and discovered freedom of thought and expression. Gradually, he found his calling and decided to exorcise the Kims’ grip through his own artistic work. By disassociating himself from the leaders, he became Sun Mu and created « his own propaganda » (3).

He paints satirical, even in some ways comical portraits of leaders. He ironically portrays Kim Jong-Un as a bearded Jesus, or links leaders with American franchises such as Disney or Coca-Cola. He goes even further in his caricature, painting a sardonic Kim Jong-Il, knife in fist, his face animated by a carnivorous smile. The leader’s glasses reflect scenes of labor and death.

Moreover, Sun Mu’s brushstrokes are not limited to denouncing the North Korean regime and the delusion in which it keeps the North Korean people. He also points the finger at the United States, Japan, Russia… all the nations involved in the separation of the peninsula, and therefore directly or indirectly linked to the rise of the Kims. The painter denounces their connivance in one of his works, « Leaders », splashing red paint on the faces of these politicians.

Although Sun Mu enjoys international renown, his path has been strewn with pitfalls. For instance, at his first exhibition in 2007, he had to face the ignorance of South Koreans, and the suspicion of the police, who questioned him, as promoting for Kim regime is prohibited in the south of the Peninsula. It was in 2014, when he returned to Beijing for a solo show, that the artist was struck by censorship. Aware of the risks, he saw his exhibition aborted by the Chinese authorities under the north-Korean government’s pressure. Knowing the inevitable presence of DPRK agents, Sun Mu had created a 5-metre-long painting with the Kim’s name written on it. Placed on the floor at the entrance of the exhibition, visitors would have had no choice but to stemple on it, thereby committing blasphemy. This misadventure was filmed during the making of the documentary « I am SunMu » released in 2015 (4).

Provocative and satirical, the artist uses his art to convey a message of hope, as seen in the painting « At Panmunjom » where Kim Jong-un and Moon Jae-in, together, hand in hand, cross the border between the two Koreas. Sun Mu breaks down boundaries and paints a complex fresco that goes beyond the black-and-white image of the Korean peninsula. He rises up like the voice of a people who have been silenced.

Notes

(1) TIVEN, Lucy, “North Korean Defector Artist Sun Mu’s Lost Utopias”, in VICE, 25.02.2019, consulté le 25.10.2023, [URL] https://sunmuart.com/north-korean-defector-artist-sun-mus-lost-utopias/

(2) LEE Yena, « Sun Mu’s satirical art : The Korean detente through the eyes of a defector », in FRANCE 24, 17.02.2018, consulté le 25.10.2023, [URL] https://sunmuart.com/sun-mus-satirical-art-the-korean-detente-through-the-eyes-of-a-defector/

(3) TAYLOR, Phoebe, “Inside Sun Mu’s Studio : From North Korean Propaganda to Satirical Art”, in theculturetrip, 6.07.2018, consulté le 25.10.2023, [URL] https://sunmuart.com/inside-sun-mus-studio-from-north-korean-propaganda-to-satirical-art/

(4) SJÖBERG, Adam, I am Sunmu, 2015, consulté le 25.10.2023, [URL] https://sunmuart.com/documentary/

Bibliographie / Bibliography

LEE Yena, « Sun Mu’s satirical art : The Korean detente through the eyes of a defector », in FRANCE 24, 17.02.2018, consulté le 25.10.2023, [URL] https://sunmuart.com/sun-mus-satirical-art-the-korean-detente-through-the-eyes-of-a-defector/

HERWEES, Tasbeeh, “Sun Mu : From propaganda to protest, one artist’s creative rebellion against the Kim regime”, in GOOD 24.03.2016, consulté le 25.10.2023, [URL] https://sunmuart.com/sun-mu-from-propaganda-to-protest-one-artists-creative-rebellion-against-the-kim-regime/

PERRAUD, Antoine, “Dans l’atelier de Sun Mu”, in Mediapart, 1.06.2018, consulté le 25.10.2023, [URL] https://sunmuart.com/dans-latelier-de-sun-mu/

REFAEL, Tabby, “North Korean Defector Sun Mu Is Turning Propaganda Art on Its Head”, in Los Angeles magazine, 5.03.2019, consulté le 25.10.2023, [URL] https://sunmuart.com/north-korean-defector-sun-mu-is-turning-propaganda-art-on-its-head/

SUN MU – The faceless painter, 30. 08. 2013, consulté le 25.10.2023, [URL] https://sunmuart.com/sun-mu-the-faceless-painter/

TAYLOR, Phoebe, “Inside Sun Mu’s Studio : From North Korean Propaganda to Satirical Art”, in theculturetrip, 6.07.2018, consulté le 25.10.2023, [URL] https://sunmuart.com/inside-sun-mus-studio-from-north-korean-propaganda-to-satirical-art/

TIVEN, Lucy, “North Korean Defector Artist Sun Mu’s Lost Utopias”, in VICE, 25.02.2019, consulté le 25.10.2023, [URL] https://sunmuart.com/north-korean-defector-artist-sun-mus-lost-utopias/

WILLIAMSON, Lucy, “Delving into North Korea’s mystical cult of personality”, in BBC News, 27.12. 2011, consulté le 25.10.2023, [URL] https://sunmuart.com/delving-into-north-koreas-mystical-cult-of-personality/

Videographie / Videography

SJÖBERG, Adam, I am Sunmu, 2015, consulté le 25.10.2023, [URL] https://sunmuart.com/documentary/

ACA project est une association française dédiée à la promotion de la connaissance de l’art contemporain asiatique, en particulier l’art contemporain chinois, coréen, japonais et d’Asie du sud-est. Grâce à notre réseau de bénévoles et de partenaires, nous publions régulièrement une newsletter, des actualités, des interviews, une base de données, et organisons des événements principalement en ligne et à Paris. Si vous aimez nos articles et nos actions, n’hésitez pas à nous soutenir par un don ou à nous écrire.

ACA project is a French association dedicated to the promotion of the knowledge about Asian contemporary art, in particular Chinese, Korea, Japanese and South-East Asian art. Thanks to our network of volunteers and partners, we publish a bimonthly newsletter, as well as news, interviews and database, and we organise or take part in events mostly online or in Paris, France. If you like our articles and our actions, feel free to support us by making a donation or writing to us.