(English version below) //

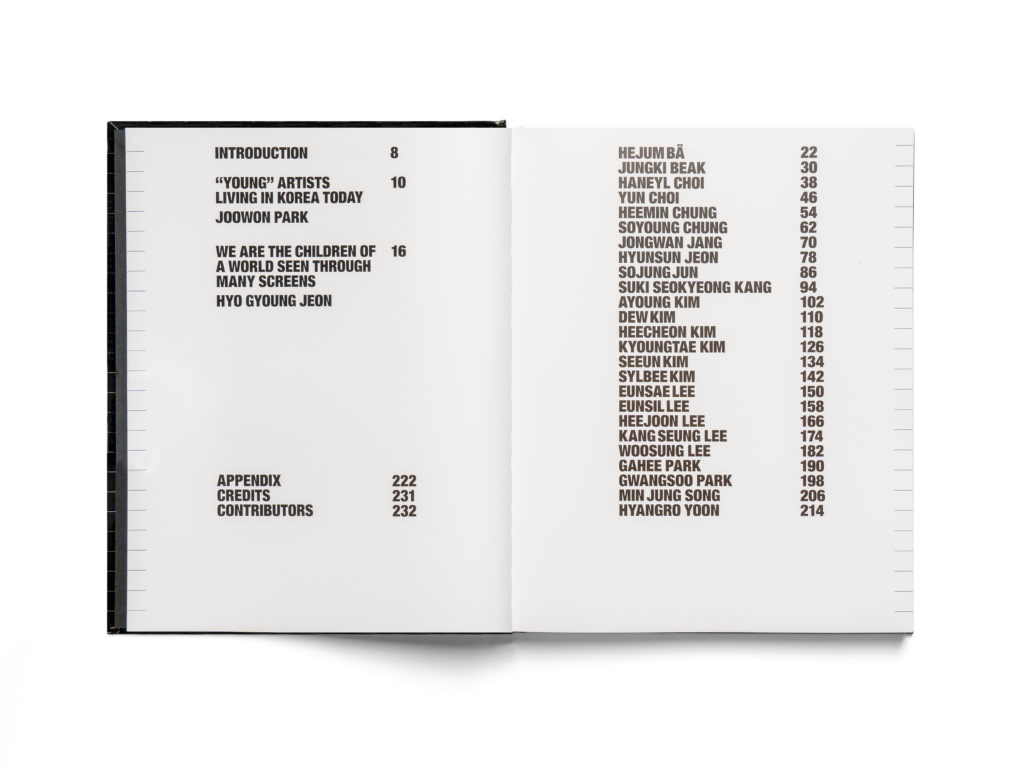

Andy St. Louis est un critique d’art et curateur spécialisé en art contemporain coréen vivant à Séoul. Il est l’éditeur de Future Present: Contemporary Korean Art, un nouvel ouvrage paru en 2024 chez Skira qui présente 25 artistes de la génération Y. ACA project l’a rencontré pour discuter de la publication de ce livre, de la scène contemporaine à Séoul, et du travail de 6 des artistes qu’il a sélectionné pour cet ouvrage.

ACA project : Bonjour Andy ! Pouvez-vous pour commencer vous présenter, et nous parler de votre rapport avec la scène artistique en Corée ?

Andy St Louis: Je vis en Corée depuis 10 ans, et j’y travaille comme curateur, critique d’art, consultant et éditeur. J’ai pendant ces 10 années beaucoup appris sur la scène coréenne, et ce livre représente l’aboutissement de ces expériences. J’avais déjà écrit à propos de beaucoup d’artistes du livre, pas sur tous, mais je connaissais bien leur travail, ayant été à des centaines d’expositions à Séoul, si ce n’est des milliers. J’ai aussi créé Seoul Art Friend, une plateforme en ligne d’archives et de ressources dédiée aux expositions à Séoul. Le milieu de l’art y est très vaste, et continue de se développer d’année en année. Je voulais donc encourager les gens à profiter de cette offre culturelle incroyable que nous avons à Séoul, et la publication de cet ouvrage va également en ce sens.

Comment est né ce projet ? Pourquoi publier un ouvrage sur l’art contemporain coréen maintenant ?

J’y pensais depuis plusieurs années. L’arrivée de Frieze à Séoul en 2022 a été un signal fort : cela montrait que le monde de l’art avait pris note de ce qu’il se passe ici, mais aussi du fait qu’il y a un écosystème très robuste en Corée, qui est remarquable non seulement dans la région, mais aussi à l’international. Il y avait déjà un fort intérêt pour l’art contemporain coréen de la part du milieu à l’international, mais les ressources accessibles en anglais sur les artistes coréens manquaient, et notamment sur la jeune génération d’artistes coréens. Je suis persuadé du potentiel qui existe pour l’art contemporain coréen dans le futur, et il me semblait que ces artistes de la génération Y [NDLR : “milléniaux”, né·es entre les années 1980 et 1990] méritaient de pouvoir avoir une plateforme qui leur permettrait d’atteindre une audience plus large.

Comment avez-vous sélectionné les 25 artistes présentés dans le livre ? Quel était votre projet curatorial ?

Je souhaitais que chaque artiste puisse bénéficier du plus grand nombre de pages possibles. Il était aussi important que la sélection se rapproche de la répartition par médiums dans l’art coréen, et la Corée n’est en cela pas différente du reste du monde, il y a davantage de peintres : il y a donc dans le livre 11 peintres, mais également 6 sculpteurs, 6 artistes vidéos, 1 photographe, et quelques artistes pluridisciplinaires. Toute sélection est subjective, mais j’ai veillé à ce que le livre soit équilibré en ce qui concerne les thèmes autour desquels les artistes travaillent, leurs méthodologies, leurs influences, etc.

Commençons par des peintres dans ce cas. Deux des artistes sélectionnées, Eunsil Lee et Gahee Park, sont des femmes peintres qui travaillent autour de médiums et techniques relativement traditionnels qu’elles mettent en perspective avec des thématiques plus contemporaines. Pouvez-vous nous parler de leur travail ?

Eunsil Lee est une peintre qui travaille un médium et emploie des techniques traditionnels, mais avec des idées très modernes. Son œuvre a toujours été extrêmement forte et audacieuse concernant son travail autour de la sexualité féminine, de la pensée traditionnelle coréenne, ses contraintes, et la manière dont cela affecte la culture contemporaine. Son travail était plus explicite quand elle était plus jeune, moins figuratif. Sa pratique a évolué pour tirer parti des propriétés uniques de médiums coréens traditionnels comme l’encre ou le papier hanji, mais toujours en les ramenant à un contexte contemporain. J’ai un profond respect pour sa force de conviction et sa manière de s’exprimer, très crue et honnête.

Gahee Park s’intéresse aussi à la sexualité. C’est une peintre figurative dont le style est surréaliste. Par certains aspects, son travail est onirique, mais il est par d’autres aussi très ancré dans la réalité tangible. Ses personnages sont principalement féminins, quoique pas toujours. Ses œuvres ne sont pas explicites en termes de contenu sexuel, mais impliquent une forte sensualité. Elle connaît bien l’histoire de l’art occidental, et fait référence à des motifs propres aux natures mortes classiques. Ce qui est vraiment étonnant dans son travail, c’est cette sensation étrange de voyeurisme qui s’en dégage, elle est à mi-chemin entre intimité et invasion de l’intimité, entre pudeur et libération complète des corps.

Passons aux deux prochains artistes, Jungki Beak et Ayoung Kim, qui expérimentent autour des sciences, du media art et de l’idée de contemporanéité. Pouvez-vous nous en dire un peu plus ?

Jungki Beak est un sculpteur qui réalise aussi des installations, mais est très conceptuel. Il s’intéresse principalement à l’intersection entre croyance et vérité empirique. Il traite souvent d’aspects de la religion populaire ou du chamanisme coréen, quoique pas de religions formalisées ou systématisées en tant que telles, et toujours en les reliant à des phénomènes naturels. Il s’intéresse beaucoup à la matérialité, et à qui fait l’essence d’une substance. Dans la culture traditionnelle coréenne par exemple, le dragon est une entité mythique qui fait office de médiateur entre les cieux et la terre, et est associé à la pluie. À partir de cela, il a créé un réacteur nucléaire miniature. La structure de la sculpture reprend cette iconographie du dragon, dans le but d’évoquer la révérence pour le dragon en tant que créature mythique qui amène la pluie de la même manière que nous vénérons l’énergie nucléaire. Ses œuvres ont toutes de nombreuses couches, et toutes me fascinent.

Ayoung Kim partage un certain nombre de ces centres d’intérêts. Elle s’intéresse à l’endroit où la croyance et la vérité divergent, et intègre de nombreux concepts comme la physique quantique ou les réalités spéculatives à ses vidéos. Mais elle s’intéresse également beaucoup aux questions sociétales autour de l’immigration, l’appropriation culturelle et le patrimoine culturel. Les mondes qu’elle conçoit dans ses œuvres vidéos ont pour but d’interroger si le monde dans lequel nous vivons actuellement est celui que nous souhaitons, et la manière dont nous pourrions analyser ce monde d’un point de vue plus humaniste. La manière dont elle articule ses idées et son approche de la narration rendent ses histoires extrêmement imaginatives. Ses compétences de réalisatrice rendent son travail réellement singulier dans le paysage des artistes multimédia coréens.

Les deux derniers artistes, Dew Kim et Haneyl Choi, travaillent tous deux sur des thématiques queers, mais en adoptant des approches différentes. Pouvez-vous nous en dire un peu plus sur leur travail ?

Je vais commencer par Haneyl Choi, qui est avant tout un sculpteur qui a une approche de son médium très formaliste. Il s’intéresse à la substance sculpturale, à la manière dont cette substance devient une forme, et dont ces deux choses ensemble créent une représentation. Son travail est très abstrait, et fait appel à un grand nombre d’idées interconnectées, principalement ayant trait à l’identité et la représentation de soi d’un point de vue queer. Il ne s’intéresse cependant pas exclusivement aux expériences queer, mais aussi aux communautés minoritaires, notamment les travailleurs immigrés, les mères célibataires, les personnes queer ou trans ; en somme, les communautés désavantagées ou victimes de discrimination ici, en Corée, comme dans le reste du monde. D’une certaine manière, il se positionne comme activiste, mais tout en faisant attention à s’effacer des œuvres qu’il crée.

C’est vrai, ce qui différencie radicalement son travail de celui de Dew Kim.

L’œuvre de Dew Kim est profondément personnelle, et fait écho à un autre aspect de la culture queer, très spécifique à la Corée. Il confronte directement les tabous qui entourent l’homosexualité en Corée. Son travail traite essentiellement du corps. Il s’oppose notamment au conservatisme chrétien par le biais d’images et de références BDSM : il fait dialoguer le concept de compassion chrétienne avec les persécutions infligées par le christianisme à diverses sous-cultures, ainsi qu’avec les idées de plaisir et de douleur propres au BDSM. Il crée ces structures métalliques complexes qui, à bien des égards, rappellent le type d’œuvres qui ornent les retables des églises catholiques. Il crée aussi des vidéos et des performances, il évolue en permanence et son travail est, je pense, extrêmement important pour le monde de l’art coréen.

Pour conclure, comment décririez-vous la scène contemporaine en Corée ? Y-a-t’il un aspect que vous trouvez particulièrement intéressant ?

Tout d’abord, lorsque l’on parle de la scène artistique coréenne, on parle en réalité de la scène séoulite. Elle est bien plus vaste que ce que les gens imaginent, il y a un nombre exorbitant d’espaces, qui continue d’augmenter. Je pense qu’il doit y avoir au moins 200 galeries à Séoul en ce moment. En ce qui concerne la production artistique, c’est comme n’importe quelle autre scène artistique très développée : les artistes travaillent de beaucoup de manière différentes, avec des méthodologies et des techniques diverses. En ce sens, la scène n’est pas différente des autres scènes artistiques contemporaines développées. Je crois qu’il y a en Corée un niveau de conscience esthétique, d’appréciation – à défaut d’un meilleur terme – pour les cultures visuelles, l’art, le design, l’architecture, la mode, plus important. Et je pense que c’est cela qui stimule la scène artistique contemporaine aujourd’hui.

Entretien mené par Erwan Jambet – Séoul, Août 2024

Andy St. Louis is a Seoul-based art critic and curator specializing in Korean contemporary art. He is the editor of « Future Present: Contemporary Korean Art », a new book published in 2024 by Skira introducing 25 Millennial Korean artists. ACA project sat down with him to discuss this new publication, the contemporary art scene in Seoul, and the work of 6 artists featured in the book.

Hi Andy! Can you start by introducing yourself and your relationship with the Korean art scene?

I’ve been living in Korea for 10 years, working as an art critic and curator, consultant, and an editor. I’ve learned a lot about the Korean scene over the 10 years that I’ve been here, and so this book is sort of a culmination of all that experience. Many of the artists in the book I’ve already written about, some of them I’ve never written about, but I definitely knew all of them quite well having gone to hundreds, if not thousands of exhibitions here in Seoul. I also founded Seoul Art Friend, an online archive and resource for discovering exhibitions in Seoul. The Seoul art world is very expansive, and continues to grow every year, so I really want to encourage the public to take advantage of this amazing cultural resource that we have here in Seoul. And this book is another step toward achieving that goal.

What was the start of this project? Why publish a book about Korean contemporary art now?

I’ve been wanting to do something like this for many years, and once Frieze came to Seoul in 2022, that was really a strong signal that the international art world was taking note of what was happening here, as well as the fact that there is a very robust art ecosystem here that is notable not only in the region, but also internationally. There was already significant interest in contemporary Korean art from the global art community, but there’s been a real absence of English language resources on Korean artists, and specifically the younger generation of Korean artists. As a person who believes very strongly in the potential for Korean contemporary art in the future, it really seemed like these artists from the Millennial Generation deserve a real platform to reach a wider audience.

How did you select the 25 artists that are featured in the book? What was your curatorial intention with this selection?

I wanted to allocate as many pages as possible for each artist. Also, it was important for the artists list to approximate the distribution of different mediums in the Korean art world. And Korea is no different from any other country, there are more painters than anything else, so I think there are 11 painters but then there are 6 sculptors, 6 video artists, one photographer, and then a few artists that are working in multiple disciplines. Any selection like this is going to be subjective, and the final considerations were made so that the book would be well rounded in terms of the themes that the artists are interested in, their methodologies, influences, etc.

Okay, so let’s start with the painters then. Two of the artists that are featured in the book are two women painters, Eunsil Lee and Gahee Park, working with rather traditional mediums or techniques that they’re putting into perspective with more contemporary issues. Can you introduce their work?

Eunsil Lee is a painter who works in very traditional medium and technique, but with very modern ideas. Her work has always been incredibly strong and bold in terms of her engagement with female sexuality as well as the constraints of traditional Korean thought and how that affects contemporary culture. When she was younger, her work was more explicit, more figurative. Her technique has really evolved to make use of the unique qualities of traditional Korean media such as ink and hanji paper, but she’s bringing it into a very contemporary context. I really respect her conviction and her continued efforts to express herself in this very raw and honest way.

Gahee Park is also interested in sexuality. She is a figurative painter whose style is surreal. In some ways, her work is dreamlike, but in other ways it’s very much based in concrete reality. Her figures are mostly female, but not always. Her works are not explicit in terms of their sexual content, but they do imply a strong sensuality. She is very aware of Western art history, and her work clearly borrows from motifs of classical still lifes. What’s really amazing about her work is this very uncanny sensation of voyeurism that you get, she’s really walking that line between privacy and invasion of privacy, between personal modesty with one’s body and complete liberation of one’s body.

Let’s move on to the next two artists, Jungki Beak and Ayoung Kim. They’re both in a way working through scientific experimentation, media art and contemporaneity. Can you tell us a bit more?

Jungki Beak is a sculptor / installation artist, but he’s very conceptual. His primary interest is the intersection of belief and empirical truth. Often, he engages with aspects of Korean folk religion and shamanism, although not formalized or systematized religion as such, and he always ties it in with some natural phenomenon. He is very interested in materiality in general, and what is the essence of a substance. For example, in traditional Korean culture, the dragon is this mythical entity that is a mediator between heaven and earth, so the dragon is associated with rainfall. However, what he did with this was he created a miniature fusion reactor, and the structure of the sculpture has all of this dragon iconography, which is meant to evoke the reverence for the dragon as this mythical creature which brings rainfall in much the same way that we have reverence for nuclear energy. All his works have so many layers, and I’m fascinated with all of them.

As for Ayoung Kim, she shares a lot of similar interests. She’s also interested in where belief and truth diverge, and incorporates a lot of different concepts to her video works, like quantum physics and speculative realities. But she’s also been very interested in social issues around immigration, cultural appropriation and cultural heritage. The worlds that she builds in her video works are really meant to question whether the world we’re living in now is the one that we want, and how we might go about analyzing this world from a more humanistic perspective. The frameworks of her stories are extremely imaginative in terms of the combination of her ideas and approach to storytelling, but also just the filmmaking skill that she has makes her work really singular among Korean video and media artists.

The last two artists are Dew Kim and Haneyl Choi, who are both working on queer issues but with different approaches. Can you tell us a bit more about their work?

Starting with Haneyl Choi, he is really a pure sculptor who approaches the medium from a very formalist background. He is interested in sculptural substance but also how that substance becomes a form, and how these two things come together to create a representation. His work is very abstract, and involves a lot of interconnected ideas, mostly about identity and self representation from a queer standpoint, although not exclusively about queer experiences. He’s interested in minority communities, including migrant workers, single mothers, queer and trans people; really, communities that are socially disadvantaged or discriminated against here in Korea as well as around the world. In some ways, he functions as an activist but he is very careful to also remove himself from the works that he creates.

Yes, which in that regard makes his work very different from Dew Kim’s.

Dew Kim’s work is deeply personal, and he is speaking to a different aspect of queer culture which is very specific to Korea. He directly confronts the taboos around homosexuality in Korea, and his work is very much about the body. One way in which he counters the conservatism of Christianity is through BDSM imagery and references. He juxtaposes the idea of Christian compassion with the persecution that Christianity commits against various subcultures, alongside the pleasure and pain that comes with BDSM. He creates these intricate metal structures that in many ways emulate the sort of work that you would see on an altarpiece in a Catholic church. He also works in video and performance, so he’s constantly evolving and his work is, I think, very important for the Korean art world.

To wrap up the interview, I was wondering how you would describe the contemporary art scene in Korea. Is there one specific aspect of it that you find especially interesting?

First of all, when we talk about the Korean art scene, we’re talking about the Seoul art scene. It’s much bigger than most people understand: the number of spaces is absolutely astronomical and continues to increase. I would say there have to be at least 200 art spaces in Seoul right now. In terms of the art that’s being created, it’s just like any highly developed art scene, artists are working in very diverse ways, different methodologies, techniques, so in that way it’s no different from any other developed contemporary art scene. I think that for the Korean audience, there’s a high level of aesthetic awareness and a greater degree of appreciation – for lack of a better word – of visual culture, art, design, architecture, fashion. And I think this is what’s driving the contemporary art scene today.

Interview by Erwan Jambet – Seoul, August 2024

ACA project est une association française dédiée à la promotion de la connaissance de l’art contemporain asiatique, en particulier l’art contemporain chinois, coréen, japonais et d’Asie du sud-est. Grâce à notre réseau de bénévoles et de partenaires, nous publions régulièrement une newsletter, des actualités, des interviews, une base de données, et organisons des événements principalement en ligne et à Paris. Si vous aimez nos articles et nos actions, n’hésitez pas à nous soutenir par un don ou à nous écrire.

ACA project is a French association dedicated to the promotion of the knowledge about Asian contemporary art, in particular Chinese, Korea, Japanese and South-East Asian art. Thanks to our network of volunteers and partners, we publish a bimonthly newsletter, as well as news, interviews and database, and we organise or take part in events mostly online or in Paris, France. If you like our articles and our actions, feel free to support us by making a donation or writing to us.