Retour sur le Roi de Kowloon, Tsang Tsou-Choi, et sa portée sur la culture Hongkongaise.

Looking back at the King of Kowloon, Tsang Tsou-Choi, and his significance in Hong Kong culture.

By Amandine Vabre Chau

English version below

Un Roi en devenir

Surnommé « Roi de Kowloon », ce personnage Hongkongais a été -et est toujours- source de débat. Tsang Tsou-Choi est né en 1921 et était éboueur avant de devenir artiste malgré lui. Actuellement exposé au musée M+ de Hong Kong, il acquit son titre en se baptisant lui-même roi de la péninsule Hong Kongaise, Kowloon.

La légende est la suivante : Tsang est en réalité le véritable souverain de Kowloon car un empereur chinois en aurait fait don à l’un de ses ancêtres, le rendant alors victime de dépossession par le gouvernement actuel. Au départ, notre protagoniste ne revendiquait que la péninsule, puis progressivement l’entièreté de Hong Kong fut concernée. Personne ne sait réellement comment cette idée lui est parvenue, l’origine de son obsession étant multiple. Certains affriment que notre protagoniste aurait découvert des documents officiels appartenant à sa famille qui attesterait de droits de propriété de son clan ancestral. D’autres relatent un accident qui le rendit handicapé et l’entraîna dans la folie. Malgré le silence de sa famille à ce sujet et le dénigrement des autorités Hong Kongaises, le ‘Roi de Kowloon’ se transforma en une icône propore à lui. En effet, il devint un des artistes Hongkongais les plus prisés et fut même inclu dans la Biennale de Venise en 2003, avant son décès en 2007.

Une histoire particulière

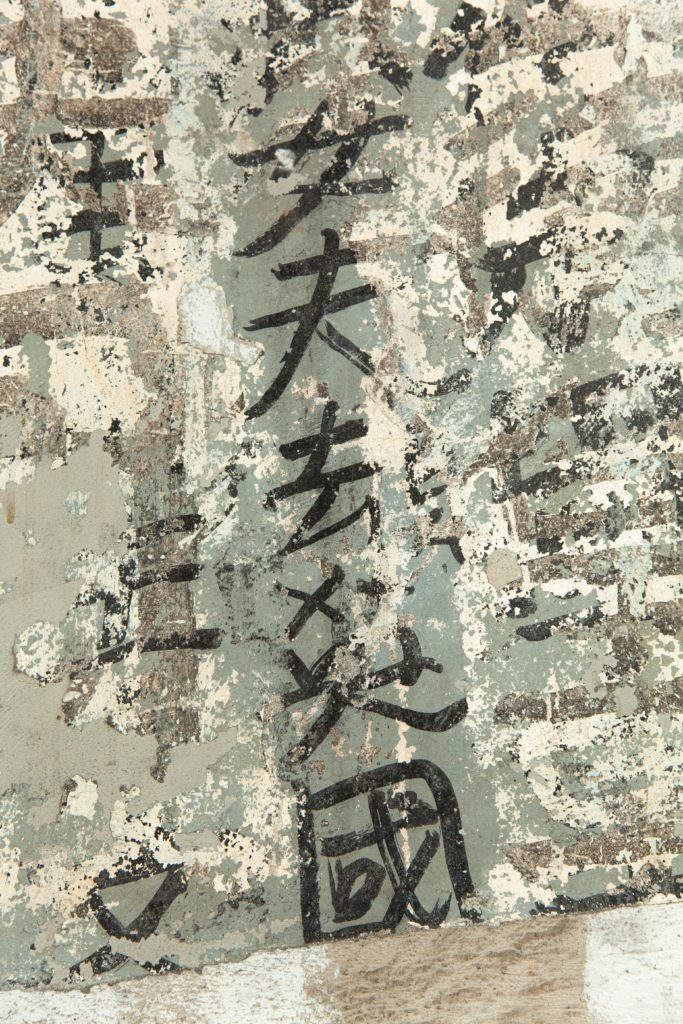

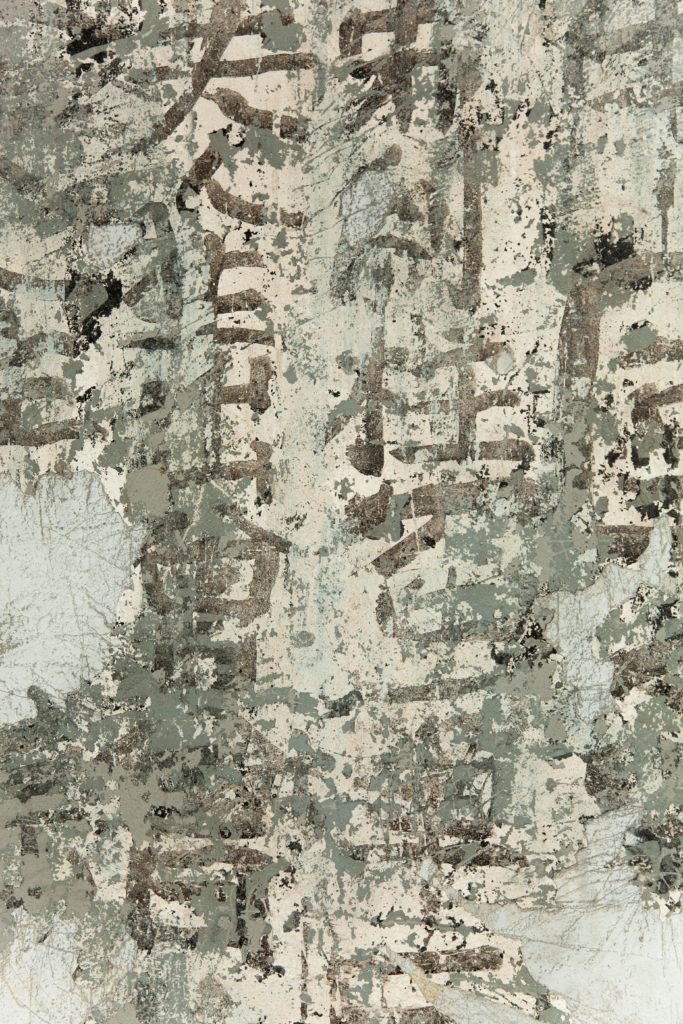

Tsang lança sa surprenante campagne à l’âge de 35 ans, comme tout bon roi fait lorsque leur territoire leur est volé : en déclarant guerre. La calligraphie fut son arme de prédilection, et la ville fut sa cible. Au milieu des années 50, armé d’un pinceau en poils de loup, il commença à peindre sur des murs, piliers, boîtes électriques, lampadaires et diverses structures appartenant à l’État. Ses supports furent choisi avec soin: il ne se focalisa que sur les édifices appartenant à la Couronne (lorsque Hong Kong était encore une colonie britannique) puis ceux appartenant au gouvernement (lorsque la ville fut restituée à la Chine, en 1997). Ni les autorités, ni le public, ne considéraient son travail comme artistique. Le gouvernement qualifiait son travail de vandalisme, tout au mieux d’ ‘écriture à l’encre’.

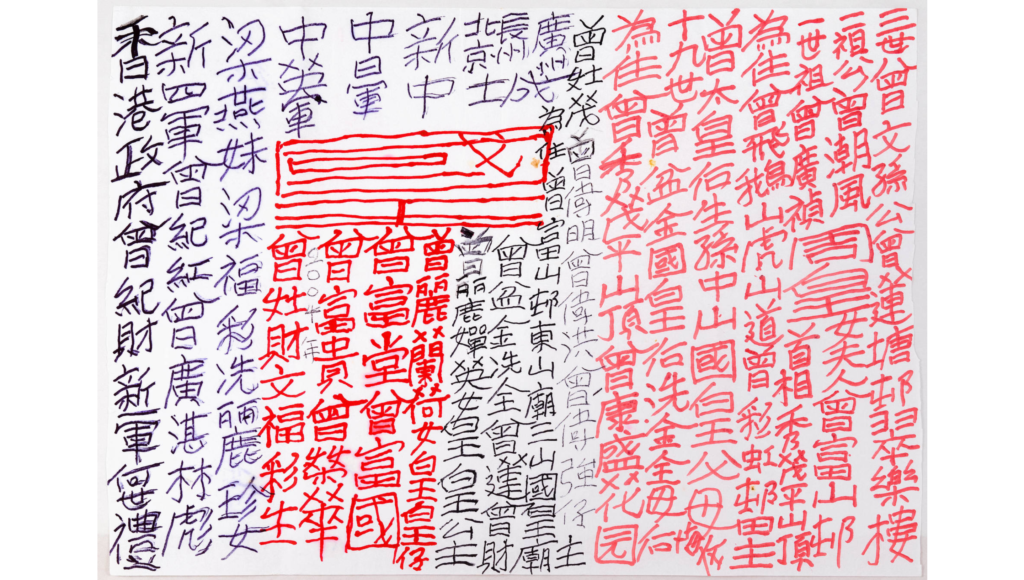

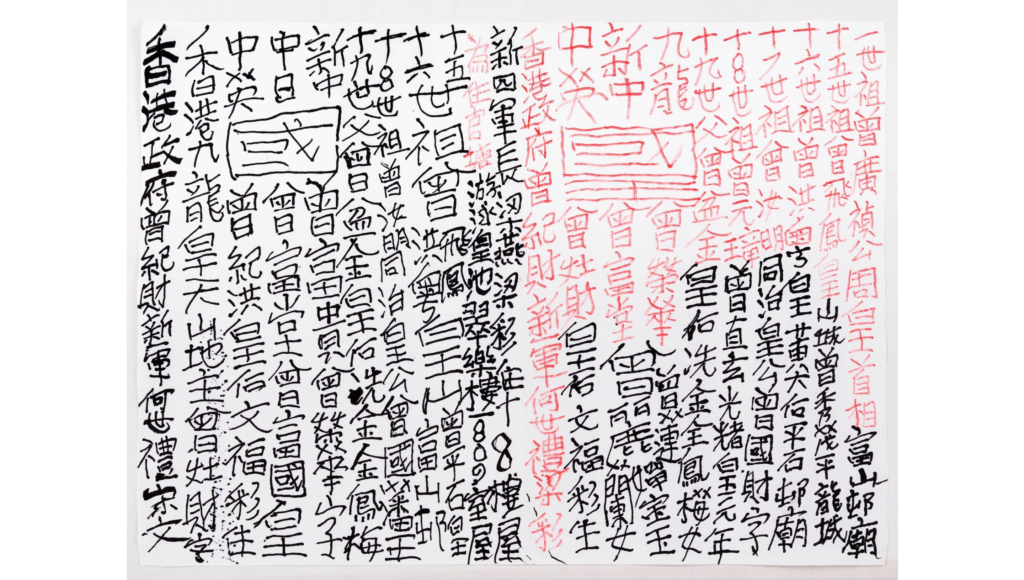

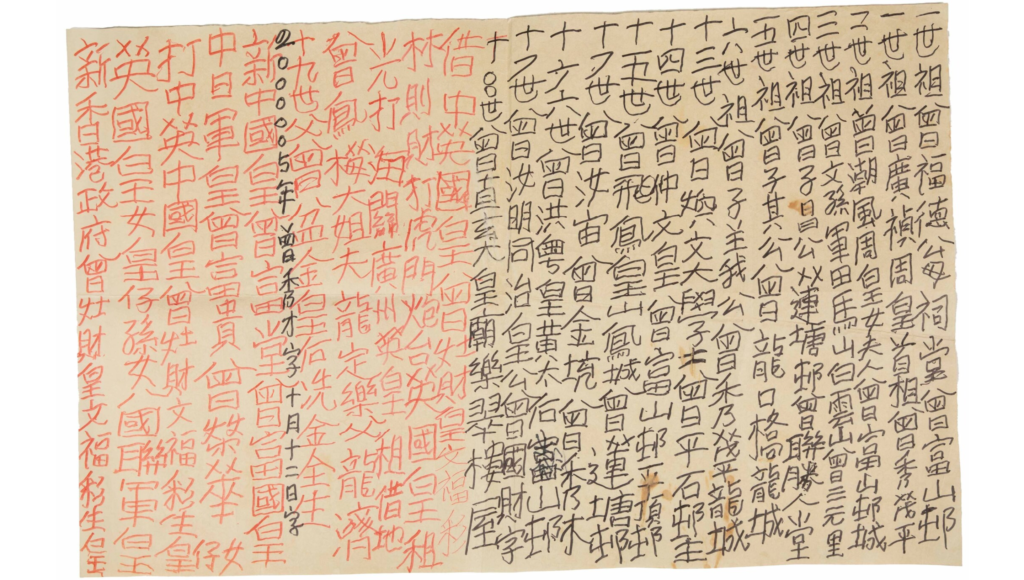

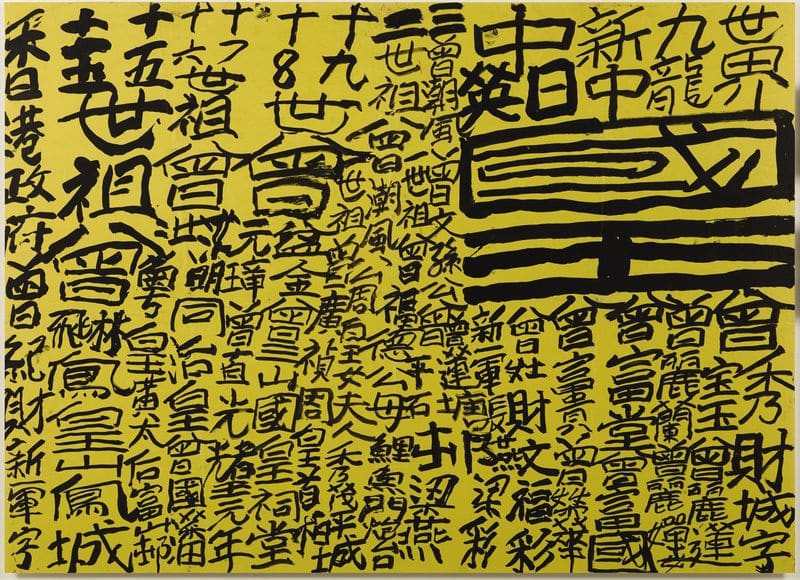

Tsang ne fut scolarisé que pendant deux ans, et ses caractères chinois se montraient donc irréguliers voir incorrects, mais jamais hésitants. Au contraire ils furent imposants, larges, visibles et absolument impossibles à ignorer. Avec 55 845 œuvres à son compte, il réussit à construire une ville à son image. Témoins de ses efforts, ses sujets assistèrent à un véritable jeu de cache-cache: chaque fois qu’une de ses nouvelles créations était effacée par les autorités, il revenait à son tour pour recouvrir la surface de nouvelles écritures. Tsang Tsou-Choi se montrait inflexible face à la suppression de son travail et était déterminé à se faire entendre. La plupart du temps, il écrivait le noms des membres de sa famille jusqu’à revenir 21 générations en arrière. Son but était de montrer à qui le gouvernement avait extirpé ce territoire. Il y ajoutait souvent son nom, des chiffres, des dates ainsi que des insultes telles que « Fuck the Queen ». Il était connu pour jouer son rôle à la perfection, demandant à se faire appeler « Votre Majesté » et réclamant même des taxes foncières au gouvernement en place.

Les Hongkongais.e.s commencèrent à se prendre d’affection pour le roi. Si ce n’est pour son talent, alors pour son impressionnante audace. En effet, Tsang fut un homme ordinaire mais aventureux qui décida contre toute attente de défier deux puissances mondiales, et ce, tous les jours jusqu’à la fin de sa vie. Il le fit sans discrétion et exhiba une provocation enfantine inconventionnelle, erratique et surprenante. Il est apparu tel un étrange phénomène issu d’une tension croissante face aux enjeux sociopolitiques de son environnement. La plus improbable des icônes, Tsang défendit ses positions en se déclarant souverain. À choisir entre artiste ou fou, il se proclama Roi.

Contexte politique et social

Hong Kong a été transmise de la Chine à la Grande-Bretagne, puis de nouveau à la Chine, en vertu d’un accord signé par les deux parties. L’Angleterre avide de thé et de porcelaine exigea une partie du territoire chinois pour y établir son commerce sous peine d’être envhie. La population locale ne fut pas consultée et cet accord fut donc signé sous la contrainte pour la Chine. Lorsque la métropole fut restituée en 1997, comme le prévoyait l’accord, le principe d’ « un pays, deux systèmes » fut mit en place. Ce principe constitutionnel stipule qu’Hong Kong doit rester inchangé pendant 50 ans, jusqu’en 2047, en conservant ses propres lois et son propre système. Suite à quoi, le territoire sera entièrement réintégré à la Chine. Le compte à rebours fut ainsi lancé. Pour simplifier le clivage en 1997 : d’un côté, certain.e.s ressentaient une nostalgie coloniale pour un soi-disant meilleur dirigeant qui a introduit un mode de vie avec d’énormes retombées capitalistes; de l’autre se trouvait les patriotes dont l’humiliation subie par la Chine resta gravée dans la mémoire. Enfin, certain.e.s ont refusé la logique binaire et s’identifièrent à une culture locale grandissante. Les revendications de Tsang Tsou-Choi prennent donc une autre importance avec ce contexte. Bien que de manière inconsciente, il réussit à se faufiler à travers les mailles du fillet et à symboliser un malaise grandissant face à ces bouleversements.

Sa pratique artistique et son symbolisme

Ce qui est considéré comme artistique ou non est constamment débattu. La definition même de l’ ‘art’ étant sujet de débat. Après tout, si notre vision de cette pratique devait rester inchangée, celle-ci régresserait. L’art change, se transforme et s’adapte. C’est pourquoi la calligraphie de Tsang est devenue un élément important de la culture visuelle de Hong Kong. Elle est apparue à un moment précis, avec une approche et une méthode spécifique répondant à son environnement. Le travail de Tsang était visuellement insolite. Il ne répondait pas aux normes traditionnelles de la calligraphie, beaucoup trop imprécis dans son exécution. Pourtant l’accumulation de ces caractères formaient au fur et à mesure des sortes d’écritures cubiques empilées les uns sur les autres. Elles envahissaient chaque surface avec une urgence, un désespoir presque maniaque d’occuper l’entièreté de la surface disponible. Une qualité surprenante sachant que le choix même de ce medium ne fut pas anodin. La calligraphie fut l’art de prédilection des empereurs chinois. L’artiste perpétua donc cette tradition en se l’appropriant. Il prenait soin de placer ses caractères de haut en bas puis de droite à gauche, formant une grille de lecture traditionnelle chinoise. Il configurait de nouvelles formes à l’intérieur de celles qui se formaient déjà sous ses yeux, agrandissant soudainement un caractère spécifique afin que celui-ci puisse attirer notre attention. Ce caractère fut presque toujours le mot « Roi ». En plaçant sa signature au premier plan, il s’assurait de son autorité visuelle.

Malheureusement, sur les 55 845 ouvrages, il n’en reste plus que trois encore visibles en public. Quelques-uns ont été retirés et placés dans des musées mais la plupart sont perdus, cachés sous d’épaisses couches d’enduit. Il existe également certains objets qu’il peignit à la demande de curateur.ice.s et diverses personnalités artistiques. Durant les dernières années de sa vie, de plus en plus de personnes se sont intéressées à son travail et sachant qu’un mur est difficilement transportable pour ensuite être revendu, certain.e.s lui ont donné des bouteilles, tee-shirts, et autres articles à décorer. Nombre de créateur.rice.s de mode, directeur.rice.s artistiques, décorateur.rice.s d’intérieur et curateur.rice.s l’ont alors rencontré, ou se sont inspiré.e.s de lui. Sa calligraphie fut bientôt retrouvée sur divers produits commerciaux et il fut même invité à figurer dans des films et à paraître dans des publicités. À juste titre, le public exprima une certaine inquiétude quant à l’éthique d’introduire une personne connue pour avoir des troubles mentaux dans un écosystème marchand sans scrupules. On pourrait aussi s’interroger sur la pertinence de lui faire écrire sur des objets alors que son but était de démontrer sa souveraineté sur les terres volées avec des œuvres publiques. Plus important encore, Tsang ne s’est jamais considéré comme artiste. Il avait à maintes reprises clarifié sa position, soit son statut de Roi. Après tout, ne serait-il pas questionnable de transformer une personne en un symbole qu’elle n’a jamais revendiqué ?

Toujours est-il que Tsang-Tsou Choi fut un homme ordinaire qui parvint à réaliser l’extraordinaire. Avec tous ses défauts et son extravagance, contre toute attente et même contre sa volonté, il offrit un aperçu de ce que l’irrationnel pouvait accomplir et s’inscrivit dans la mémoire collective de la ville.

A King in the making

Known as the « King of Kowloon », this Hong Kong figure was -and still is- conflicting for many people. Born in 1921, Tsang Tsou-Choi was a garbage collector turned artist against his will. Currently exhibited at M+ Hong Kong, he earned his title by baptising himself the rightful king of the Hong Kong Kowloon peninsula.

The story goes like this: Tsang is the rightful king of Kowloon as the territory was given to one of his ancestors by a Chinese Emperor. At first only referring to the peninsula, he soon considered the entirety of Hong Kong his. No one knows for sure how he came to believe so and there has been varying reports of his obsession’s origin. One of these states that he found family documents testifying his ancestral clan’s ownership over the territory. Another, more common, says it was due to an accident which rendered him disabled and led to mental health issues. His family stayed out of the spotlight and officials never recognised his claims. None of this stopped our protagonist from becoming a Hong Kong cultural icon, even leading to his inclusion at the 2003 Venice Biennale, before his passing in 2007.

An unexpected tale of defiance

He began his campaign at 35 years old, starting as all good Kings do when land is stolen from them: by declaring war. Calligraphy was Tsang’s weapon of choice and the city was his canvas. In the mid-50s, armed with a wolf-hair brush, he began writing in public spaces. Mostly walls, pillars, electricity boxes, lampposts and various government-owned structures. Indeed, he picked carefully by only targeting crown land (when Hong Kong was a British Colony) then government land (when it returned to China in 1997). At first, neither the Authorities nor the public considered his work art, instead calling it vandalism or ‘ink writing’ at best.

Having attended school for only two years, his Chinese characters were irregular and occasionally incorrect but never hesitant. Instead, they were imposing, big, visible, and absolutely impossible to ignore. With an estimated 55 845 works in public spaces, he managed to build a city in his own image. Bearing witness to his endeavours, his subjects saw him play a masterful game of graphic hide and seek with the government. Each time one of his new creations was painted over by government cleaners, he would come back to cover the entire surface again. Tsang Tsou-Choi was unyielding when confronted with the erasure of his work. Determined to be heard and have the world witness his loss, he would write all 21 generations of his lineage to explicit who the government stole from. Adding his name, numbers, significant dates along with insults such as “Fuck the Queen”, he would also ask people to refer to him as “Your Majesty” and occasionally ask the ruling powers -which he called imposters- to pay him land taxes.

Hong Kongers began to slowly but surely take a liking to the King. If not for his debatable talent, at least for his sheer audacity. A comical tale at times, an awe inspiring one at others. A man, bold and reckless, somehow decided to challenge two global superpowers every day for the rest of his life. Furthermore, he did so without being discreet and chose an unconventional eruption of childlike provocation. It appeared as if he was an organic byproduct of the larger socio-political issues in Hong Kong, resulting from a mounting tension felt by many. The most unlikely of icons, a product of the absurdity of his time. Instead of artist or fool, he chose the title of King.

Political context and social background

Hong Kong was passed on from China to Britain and back to China again under a coerced agreement signed by both parties where the inhabitants of Hong Kong were not consulted. Britain, hungry for tea and porcelain, required China to cede part of its territory for trade unless they were to face invasion. When the metropolis was returned to China in 1997, as the former agreement stated, the ruling powers agreed on the “One Country, Two System” principle. A constitutional principle declaring that Hong Kong was to remain unchanged for 50 years, continuing with its own laws and system developed under the British empire, until 2047 when it will be returned to China in full. This effectively activated a countdown until the end of this purgatory. To simplify the divide in 1997: on one hand some had colonial nostalgia for a supposedly better ruler that introduced a way of life with capitalistic characteristics; on the other were patriots who remembered very clearly the century long humiliation China endured at the hands of European colonisers. Then, some refused the either/or logic and identified with a growing local culture. With this context, the significance of Tsang Tsou-Choi takes on another meaning. Even if unconsciously, he managed to slip between the cracks of the system and embody a growing sense of discomfort.

Artistic practice and its symbolism

Our conception of art is reevaluated every now and then, as it should. If our interpretation was to remain unchanged, the art world would regress. Art is bound to change, transform and adapt to its times. That is why Tsang’s calligraphy came to be an important part of Hong Kong visual culture. It emerged at a specific time with a specific approach in echo to his larger environment. His work was visually bold and bizarre. It did not conform to traditional calligraphy standards, too imprecise in its execution. Yet the accumulation of his thick characters, stacked on top of one other and forming an ensemble of strange cubic writing, invaded every surface with an impossible urge. A surprising quality coupled with a calculated choice in his medium. Indeed, calligraphy was an Emperor’s art, and Tsang continue this tradition by reappropriating it. He was careful to place his characters from top to bottom and from right to left, making sure his pieces were read in the Chinese traditional way. He calculated the size of his words, enlarging certain characters to take up the space of 5, drawing your attention to it. This character, almost always read “King”. Placing his signature front and center, you were to witness his visual takeover.

Unfortunately, out of the 55 845 works, only three survived in public spaces. A few were transported to museums along with some objects he painted on after people asked him to. In his final years, more and more people got interested in his work. As walls are difficultly removed to sell, some gave him bottles, tee-shirts, and other items to write on. More and more fashion designers, art directors, interior decorators and curators met with him. His calligraphy was soon found on various commodities and he was even featured in movies and commercials. Rightfully so, the public expressed ethical concerns about bringing a person with mental health issues into an unscrupulous commercial ecosystem. We could also question the relevance of having him write on these objects when his purpose was to demonstrate his dominion over stolen land with massive public works. More significantly, there was the fact that Tsang never considered himself an artist. He had clarified his stance on numerous occasions, maintaining his status as a wronged King. After all, isn’t it questionable to turn a living person into a symbol they have never claimed?

Still, Tsang-Tsou Choi spoke to people by being an ordinary man who achieved the extraordinary. With his flaws and peculiarity, against all odds and even against his will, he offered a glimpse of what irrationality could accomplish, and was engraved into our collective memory for doing so.

ACA project est une association française dédiée à la promotion de la connaissance de l’art contemporain asiatique, en particulier l’art contemporain chinois, coréen, japonais et d’Asie du sud-est. Grâce à notre réseau de bénévoles et de partenaires, nous publions régulièrement une newsletter, des actualités, des interviews, une base de données, et organisons des événements principalement en ligne et à Paris. Si vous aimez nos articles et nos actions, n’hésitez pas à nous soutenir par un don ou à nous écrire.

ACA project is a French association dedicated to the promotion of the knowledge about Asian contemporary art, in particular Chinese, Korea, Japanese and South-East Asian art. Thanks to our network of volunteers and partners, we publish a bimonthly newsletter, as well as news, interviews and database, and we organise or take part in events mostly online or in Paris, France. If you like our articles and our actions, feel free to support us by making a donation or writing to us.